Do you know what an anachronism is? They’re very clear in cultural terms: Shakespeare’s clocks in Julius Caesar, for example. But in historical terms, it’s a different matter. When His Majesty King Charles III was crowned, the online scoffers were quick to mobilise themselves. One enthusiastic Jacobin tweeted that the enthroned, orbed and sceptred sovereign was ‘insane’, an ‘anachronism’. Out the scoffers troop, reliably, at every State Opening of Parliament. (And quite right too: mockery is a vital part of a successful polity). ‘How Ruritanian!’ they sneer (not quite grasping that the Ruritanians were copying us. And also, er, fictional.) The jeerers usually finish by wondering why we can’t be a grown-up country, like that entirely stable republic, France. But the 5th French Republic is a tad more recent, a mere mewling infant. The scoffers have it the wrong way round. When they huff about a custom being an anachronism, what they’re essentially saying is: ‘This doesn’t accord with my politics.’ It’s a lazy argument, masking a desire for abolition or control.

Far from being ‘out of time’, our sovereign is the most chronistic, if you like, symbol possible

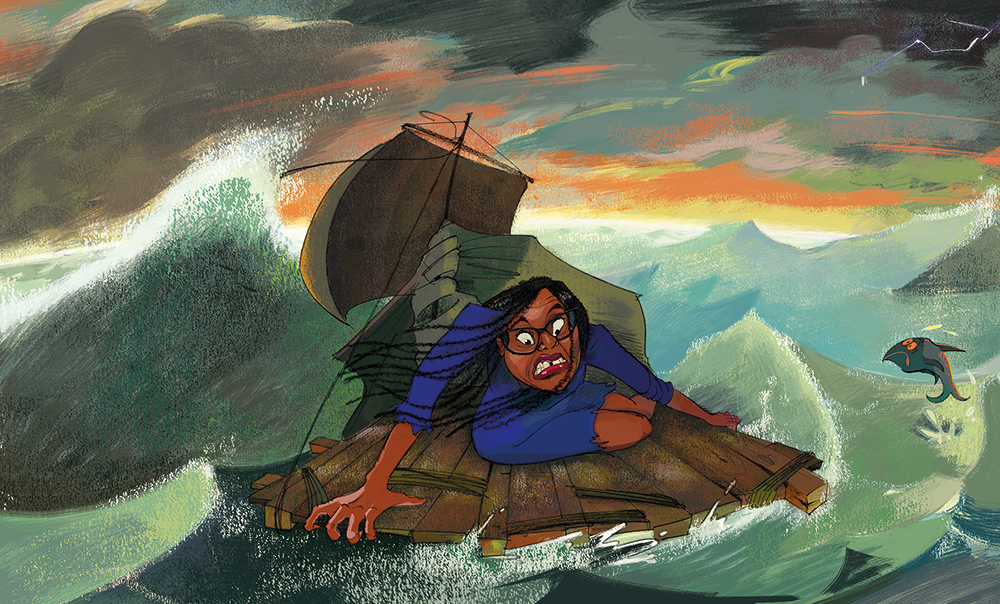

If you were a time traveller from any point in history since the Romans, and you happened to stumble into Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, you would immediately understand the scene. Here is a king, and here he is, being crowned. Far from being ‘out of time’, our sovereign is the most chronistic, if you like, symbol possible. If a living continuation of a line stretching from beyond Athelstan to the 21st century isn’t the opposite of ‘anachronous’, I don’t know what is. If your time traveller were to gawp at the official ceremonies of, say, the European Parliament, she’d be totally clueless. ‘You have just arrived on the Moon… your hands become fish… You discover a new planet. Here, plants have taken power,’ murmured a choreographer at a recent European conference. Remind me who’s insane?

The very same argument is trotted out when it comes to the remaining 92 hereditary peers in the House of Lords. They are an embarrassment! How could a ‘grown-up’ country countenance such things? The Guardian helpfully pointed out that they were all white men, and most of them were quite old. (A vital piece of reporting, there.) It is ironic that had the hereditaries remained in situ, the 5th and 6th Baron Sinhas would have taken their seats, as would Baroness Howard de Walden and the other peers whose titles pass down the female line. And had the first black life peers, Baron Constantine and Baron Pitt of Hampstead, been honoured with hereditary peerages, we might have seen their descendants there too.

Over the past 40 years, the aristocracy has changed, alongside the rest of us. An anthropological study of the House of Lords noted that hereditary peers were found toiling in all kinds of fields, from police officer to art dealer to nurse. There was even an electrician (which, given the state of the parliamentary buildings, they’d be jolly grateful for now). The hereditary principle allows for randomness: it’s a kind of sortition. Study the heirs of the current crop of aristos, and you’ll find them engaging in an equally broad range of activities, reflecting the occupations and ideas of the general public more closely than the new bunch of MPs. Have you looked them up? They’re mostly local councillors, with as much experience of ‘real life’ as cosseted Georgian toffs.

Inevitably, the remainder of the House of Lords will be padded out with political cronies. Why don’t its critics mind that, as much as they mind the hereditaries? Well. Control, you see. You can instruct Anne Smith MP: when she becomes Baroness Smith, you’ve elevated her, and she’s beholden to you. But it’s harder to make a Marxist marquess or a dentist duke say what you want them to say. These can ask questions others might not dare to utter.

The ancient customs and systems of the United Kingdom offer beauty, use and even pride, and they do so for a reason. Our county boundaries were set down by King Alfred the Great. Despite attempts at mutilation (by a Conservative, since that party can be as dismissive of tradition as the left), they are largely still in place, loved by the majority. Yet they are on their way out. Why bother, when you’ve got postcodes and What3Words? The Royal Mint was founded in AD 886. It’s seen off Saxons, Normans, civil wars and revolutions. Now, though, coins are old hat, because we can zap for our pumpkin lattes with our watches, like some bovine cosplaying Trekkie. Abolish the counties, and you’ll disturb people’s sense of local pride, which can be replaced with whatever you might have in mind. Abolish coins, and not only do you lose a daily reminder of the history of the country, but also: shazzam! The government can snoop on every single financial transaction, and tax and sanction at its whim.

And that, really, is why the scoffers call things anachronistic. Because what is supposedly so is in reality a reminder of the unusual strength of our continuous heritage; and so cleaving to those things becomes revolutionary. It’s time for our politicians, of all stripes, to look at why things last for so long, instead of seeking to alter them beyond all recognition. After all, today’s fad is tomorrow’s embarrassment. I’ll take flying the county flags over my hands becoming fish, any day.

Comments