No matter how much you love music, going to a piano recital can be an uncomfortable experience. A sombre-faced pianist plays in an atmosphere of hushed reverence, perhaps swaying and grimacing to simulate profundity. If a sonata is performed, outbreaks of guilty coughing will occur throughout the audience between movements. It’s an unwritten rule that clapping’s only permissible at the end. When the concert’s over, the pianist walks off stage after a couple of stiff bows, without ever having said a word, and everyone can finally breathe again.

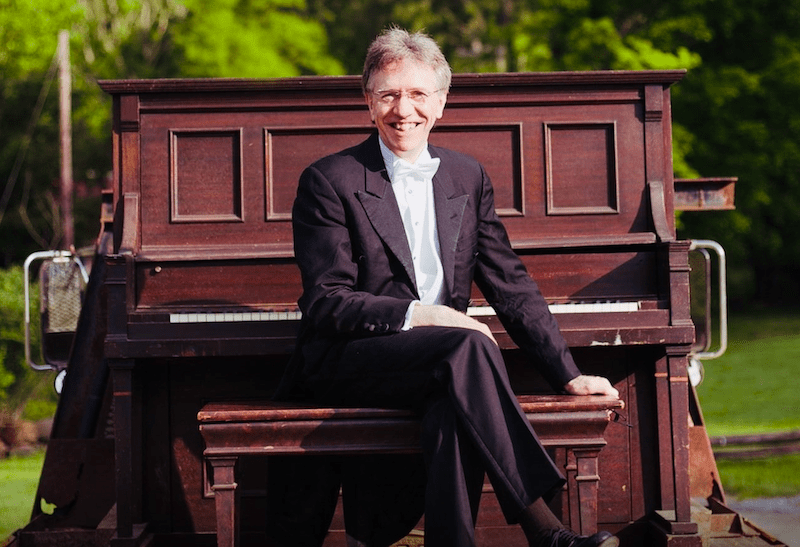

The annual series of summer piano recitals performed in Oxford by British pianist Jack Gibbons is nothing like that. Now in its 36th year, the series consists of weekly and bi-weekly recitals in the 18th century Holywell Music Room, part of Wadham College and Europe’s oldest purpose-built concert hall. This intimate venue (capacity 200) is conveniently located opposite one of Oxford’s best pubs, the Turf Tavern, to which Gibbons often retires afterwards for a pint. The last time I attended one of these concerts, anyone who wanted to was welcome to join him.

Each programme is themed around one or two composers: the next is on Wednesday and dedicated to Debussy and Ravel. There are always at least a couple focused on Gibbons’ unusual specialisms, one of which is the solo piano music of George Gershwin. Gibbons reconstructed these joyful, vibrant (and fiendishly difficult) pieces note-for-note from Gershwin’s 1920s piano rolls – an incredible feat of patience and listening in itself. He plays them with such accuracy and vigour that the composer’s biographer, Edward Jablonski, once said that hearing Gibbons play ‘is like being at a Gershwin party, in a sense like being with Gershwin’.

Gibbons’ other speciality is a strange, obscure composer named Charles Valentin Alkan, who lived next to Chopin in Paris in the 1830s and wrote piano music just as beautiful as his more famous neighbour – only much harder and weirder. Alkan’s gigantic masterpiece, which Gibbons sometimes performs during the Oxford series, is the Concerto for Solo Piano – a three-movement, hour-long piece in which the pianist plays not only the piano parts but all the orchestral elements too. It contains some of the most dramatic and haunting piano music ever written.

Between pieces, Gibbons actually talks to his audience, something that I have never seen another classical pianist do in more than 20 years of attending recitals. With enthusiasm and erudition, he sets the pieces in the context of the composers’ lives and tells anecdotes and jokes. The churchy atmosphere that usually characterises a classical piano recital is replaced by that of a private party. Applause is welcome at any time, and sometimes occurs in the middle of pieces. Coughs needn’t be chocked back. Stifling high-art etiquette doesn’t apply.

Even more fascinating are Gibbons’ deconstructions of the music. At least once during a concert, he’ll show the audience, slowly and separately, what the right and left hands are doing in the piece he’s about to perform. This is especially revealing when applied to Gershwin’s music, in which the left hand often bounces around in a different time signature to the right. ‘Then you just put them together’, he’ll say with a sideways grin, ‘like this’ – before rattling off a few virtuoso bars. Audiences love it.

Between pieces, Gibbons actually talks to his audience

It’s in these mini-lessons that Gibbons might mention the car crash in which he was almost killed in March 2001, after which he had to re-learn his craft (as well as several other horrific injuries, his left arm was shattered in fifteen places). I attended one of the first concerts he gave in Oxford after recovering from the accident, at which he joked that he was still fudging some left-hand parts because he hadn’t regained full sensation in that hand. One of the surgeons who rebuilt Gibbons’ arm said that he had come within a millimeter of permanently losing the use of his left-hand fingers.

Gibbons finishes every series with a ‘Farewell Piano Party’, at which there is no set programme, only audience requests and his own spontaneous choices (this year it’s on 14 August). He’ll often perform one of his favourite encore pieces: Vladmir Horowitz’s sadistic arrangement of John Philip Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever, an exuberant rampage that stretches even pianists of Gibbons’ calibre. Before launching into it at one Holywell recital about 15 years ago, Gibbons turned to the audience and said, again with that grin: ‘I hope you enjoy this more than I do’. But it’s the fact that audiences enjoy these recitals just as much as Gibbons does that makes them so special.

Comments