The Nakba – Arabic for ‘the catastrophe’ and commemorated today – marks a profound moment of trauma in the Palestinian Arab consciousness. In 1948, following the Arab world’s rejection of the United Nations’ partition plan and their subsequent military assault on the fledgling State of Israel, around 700,000 Palestinians were displaced. While Israel accepted the partition and declared independence, the Arab states and local militias initiated a war they would lose. Yet the memory of the Nakba, though born from an aggressive campaign that ended in defeat, has been carefully curated into a narrative of pure victimhood, a perennial wound severed from the choices and actions that preceded it.

This phenomenon is not unique to the Palestinian case. Across history, defeated peoples have frequently transformed military or political collapse into mythic narratives of victimhood, often eliding their own agency or culpability. In recent decades, scholars of memory and historiography have increasingly examined how such ‘defeat mythologies’ function – not to recount events faithfully, but to console, unify, and morally rehabilitate.

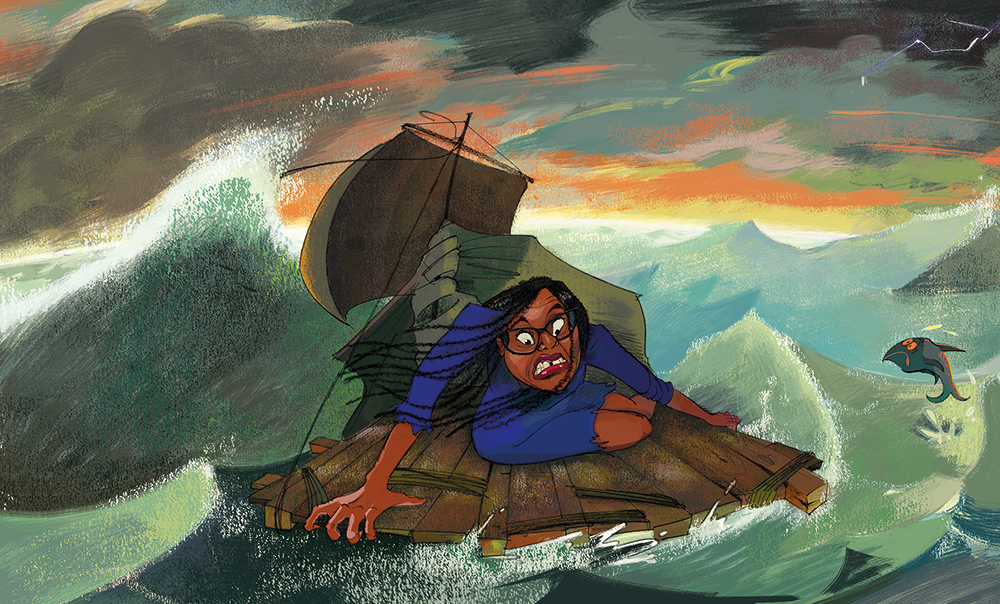

For groups like Hamas, the establishment of Israel is akin to the Crusader states of the Middle Ages

After the second world war, for example, the Sudeten Germans, who had clamoured for the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia, were expelled en masse. Though many had welcomed Hitler’s armies, their post-war suffering was later recast in humanitarian terms, abstracted from the context of collaboration. Following the Greco-Turkish War, the Greeks of Smyrna, who had marched into Anatolia with dreams of empire, lamented their catastrophic expulsion as a tragic severing from ancestral lands. Even the American South, after seceding and plunging the nation into civil war to preserve slavery, transfigured its defeat into the ‘Lost Cause’ – a durable mythology of noble gentility wronged by history.

This is not to claim that the ideologies were identical or that the suffering was equal – each case is historically and morally distinct. But the narrative arc is recognisable. While descendants and popular memory often cling to romanticised accounts of loss, critical scholarship has tended to interrogate these stories, revealing how the work of mourning can shade imperceptibly into the work of myth-making. The Nakba, too, fits within this pattern: a war initiated, a defeat suffered, and a transformation of collective memory into grievance, increasingly unmoored from the question of responsibility.

Within the broader Muslim world, this pattern of interpreting political defeat as a sacred humiliation has been even more pronounced. The collapse of the Ottoman Caliphate following the first world war was not seen merely as the end of an empire but as a theological calamity.

Movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood were born out of this moment, viewing the political subjugation of Muslims as divine punishment for collective moral decay. Their solution was not diplomacy, not secular nationalism, but a return to jihad and religious renewal to return glory to the Islamic empire. Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and the swift international response were similarly reframed by many as yet another imperialist humiliation of the Muslim world, with little reflection on Iraq’s own culpability. The devastating defeat of Arab armies in the Six-Day War was likewise interpreted not as the fruit of reckless brinkmanship but as a profound insult to Islamic honour, fuelling a potent blend of grievance and religiosity that persists to this day. While these were not the only interpretations, time and again, when the secular project failed, the holy grievance reflex stepped in to explain why.

At the heart of this theological reading of history is a deep conviction that military defeat signals divine displeasure. The Qur’anic verse ‘whatever misfortune befalls you is because of what your own hands have earned’ has been used to reflect this idea. In this line of thinking, losses are not accidents of geopolitics; they are cosmic verdicts. The proper response, in this view, is not compromise but repentance – and, crucially, the renewal of jihad as a sacred duty: only through Islamic governance and renewed piety can true victory be achieved.

It is from this soil that modern jihadist ideologies have sprung. Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, warned that Muslim dishonour flowed directly from abandoning holy struggle. Osama bin Laden, echoing the same logic, framed his war against the West as an attempt to restore the dignity of a humiliated Islamic world, not out of hatred but out of perceived religious obligation.

Within this framework, the existence of Israel – and more specifically, the sovereignty of Jews over Jerusalem – becomes an unbearable theological insult. Under traditional Islamic rule, Jews had lived as dhimmis, tolerated but subordinated. Their rise to power, military success, and control over land once part of the Islamic ummah is experienced by many not merely as a political reversal but as a violation of divine order. Radical preachers have long invoked Qur’anic verses depicting Jews as cursed, weaponising ancient theological tropes to justify unrelenting hostility. Even the oft-repeated claim that ‘Al-Aqsa is in danger’, regardless of factual basis, taps into this deeper sense of cosmic disorder: that Muslim dignity itself has been defiled by the continued existence of Jewish sovereignty.

In this eschatological vision, Israel is not a permanent state to be grudgingly accepted, but a temporary aberration destined for destruction. Islamic eschatology, particularly hadiths that predict a final apocalyptic battle between Muslims and Jews, fuels the belief that Israel’s eradication is both inevitable and divinely mandated. For groups like Hamas, the establishment of Israel is akin to the Crusader states of the Middle Ages: a foreign intrusion that will, sooner or later, be swept away by righteous force. No political agreement, no matter how carefully negotiated, can override what is believed to be the arc of sacred destiny.

Thus, the Nakba is not merely a political grievance. It has been transfigured into a sacred wound, a living symbol of dishonour that demands redress through religious struggle. Under Islamic influence, the land of ‘Palestine’ is not just contested territory – it is a waqf, a sacred trust consecrated for Muslims until the end of time, inalienable by human agreement or negotiation. To recognise Israel’s legitimacy would be to acquiesce to a theological defeat as well as a political one.

This is why the Israeli conflict with the Palestinian Arabs is not merely a struggle over borders, rights, or resources, but a confrontation rooted in existential and theological perceptions of justice, honour, and destiny. Understanding this deeper religious framework is crucial to grasping why the conflict resists conventional solutions. Until the theological dimensions of the Nakba and its aftermath are acknowledged, diplomatic efforts will continue to founder against the unyielding belief that compromise is not only a betrayal of the past but an affront to the divine.

Comments