Our immiseration came swiftly and stealthily. At the start of the 21st century, Britain was a prosperous country. Ambitious people fought to come here. We trusted that, over time, we would become wealthier – an expectation that had been accurate for most of the previous two centuries.

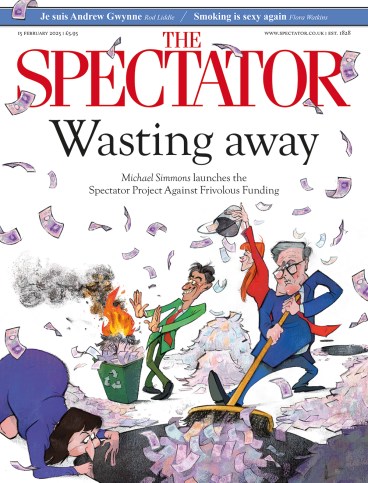

Since the millennium, Britain and western Europe have pretty much stopped growing – especially if we ignore the impact of immigration and calculate GDP per head. Reversing this slowdown should be the top issue at every election, but it is surprisingly under-discussed. In theory, almost all our politicians want growth. Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves keep describing it, nasally and tautologically, as their ‘number one priority’. Yet so far they have doled out more of the medicine that sickened the patient under the last government.

What medicine? Jon Moynihan spells it out in pitiless detail. We became poor because we enlarged the government, raised taxes and over-regulated. Well duh, you might say: there needs no ghost, my Lord, come from the grave to tell us this. But, although the diagnosis might strike you as obvious, the treatment is so unpalatable that many turn in desperation to quack cures. Rather than cutting spending, freeing markets, abolishing quangos, scrapping monopolies, lowering taxes and protecting the value of the currency, politicians pretend that our problems can be solved by some witchdoctor alternative. Crack down on fraud! Use more AI! Join the customs union!

What makes this book so valuable is its relentless empiricism. Moynihan is an entrepreneur who came relatively late to politics via chairing Vote Leave – something he did with the same unfussy efficiency that helped him to succeed in business. He is not peddling a cleverdick new theory. He is taking the best data out there, and using them to construct a calm and comprehensive case. His arguments are aimed at the intelligent but ignorant reader. He assumes no knowledge of economics. The style is reminiscent of a leader in the Economist. The result is a definitive statement of the case for growth. Originally planned as a pamphlet, the work has run to two volumes.

We are spending around £25 billion more than a country with our level of GDP should on the NHS

Volume I, published last year, set out the three big negatives. First, the state has gone from taking 34 per cent of GDP at the turn of the century to 45 per cent, leaving fewer people creating wealth and more consuming it. Second, taxes have risen to the point where investment becomes unattractive. Third, a profusion of quangos and regulators means that businesses spend more and more time doing things other than generating a profit.

Now Volume II suggests three potential positives: open competition, free trade and sound money. Again, you might be thinking et alors? But that is because you have not seen the terrifying figures compiled in these books. If you had, you would grasp the urgency of our situation.

We are becoming poorer not because our population is ageing, nor because we are admitting unproductive migrants, nor even because of lockdown – though God knows that was expensive enough. No, we are becoming poorer because we keep choosing to increase spending, taxes and debt rather than incur any short-term discomfort. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves, that we are underlings. ‘We all know what to do,’ said the bibulous Jean-Claude Juncker after the financial crisis. ‘We just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it.’ Quite. Candidates offering sweet delusions generally beat those peddling hard truths.

Rightists pretend that huge sums can be squeezed from the foreign aid budget, leftists from defence. But, as Moynihan shows, the relentless rise in spending is largely in social security and healthcare (we are spending around £25 billion a year more than a country with our level of GDP should on the NHS). Politicians who won’t cut these budgets don’t really want to cut spending. Given the depressing response of both the Tories and Reform to Labour’s removal of the winter fuel allowance, we are still nowhere near recognising the scale of the problem.

Perhaps we must collapse completely before we pick ourselves up. It took a century of decline to persuade Argentines to vote for Javier Milei. Ireland had to make deep cuts in public sector pay and benefits during the euro crisis – cuts which paved the way for a decade of strong growth. Then again we could reverse much of our economic decline simply by returning public spending to where it stood during the early Blair years. Most of us can remember that time well enough. We were hardly a Dickensian sweatshop. The way to growth is not easy, but it is simple.

Comments