Michael Gove has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Shabana Mahmood may be the only Labour politician to have persuaded Rishi Sunak to vote for her. The former prime minister was in the year above Mahmood when they both studied at Lincoln College, Oxford, in the 1990s. When she ran for JCR president, Sunak pledged his support. Meeting Mahmood in her ministerial office this week, I can understand why. There is a sense of quiet purpose about her that instils confidence.

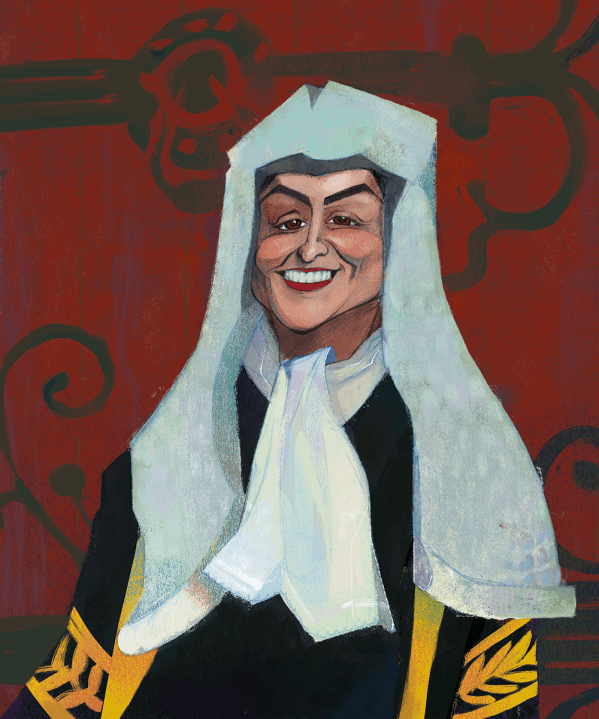

I’m predisposed to sympathise with her more than most because she occupies the post I held for 15 months – Lord Chancellor. It’s the most glamorous and least attractive job in the cabinet. You’re the only minister with your own personal gold-braided gown, wig, pumps and purse bearer – or at least the only one who has to be seen with all four publicly. But you’re also in charge of prisons. The care of 90,000 souls – who are simultaneously the most broken and most dangerous in society – is your responsibility.

Prisons have been in crisis for years. Few holders of the office in recent times have prospered politically. I was sacked from the role, and my two predecessors were demoted, as were most of my successors.

So it takes resilience to survive in the role, let alone succeed. Does the incumbent have what it takes? Mahmood, who is 44 and MP for Birmingham Ladywood as well as a former barrister, has been in post for less than a year. Already she has had to authorise a controversial early release scheme for prisoners and confront the judiciary over sentencing policy. But her battles have only started. Sitting in the 9th-floor Westminster office I once occupied, she seems serene but her analysis is stark.

‘I’m looking at zero prison capacity in a few months’ time. It’s not acceptable to me. So we’ve got to get out of this permanent crisis,’ Mahmood says. ‘We’ve got to never be in a position where governments of all stripes have to do emergency releases. And it falls to me to make sure we get that right. My biggest duty in this job is to stop this system from being permanently on the brink of collapse.’

Facing the prospect of a prison estate in which there is – literally – no room for new inmates, she has to contemplate radical measures. A review of sentencing policy she commissioned from David Gauke, the former Tory Lord Chancellor, is due shortly. He will recommend earlier release for prisoners who undertake rehabilitation and exhibit good behaviour. Yet in Mahmood’s view the situation is so concerning that she will have to take radical action well before any of his recommendations can be enacted.

‘You can take a big decision, like an early release step as I had to do,’ she says, ‘and it still doesn’t buy you enough time. You’re still on the verge of running out.’

‘I’ve got a job to do. That’s the only thing I’m focused on. I’ve taken a solemn oath on my holy book’

Part of the answer, she says, will be an expansion of community sentences: ‘We’ve got to expand the range of punishment outside prison. In a world where we are always running out of prison capacity, we have to think about those offenders who can be effectively managed in the community.’

Public confidence in community sentences is low, with offenders capable of absconding and probation services stretched. But Mahmood believes technology can ensure compliance in a way which reassures people. ‘The next generation of tech and AI can ultimately more effectively manage prisoners,’ she says, ‘because the eyes of the state can always be on you, checking your behaviour.’

Liberals might shiver. However, Mahmood isn’t concerned, and nor is she worried about the political cost. ‘It’s not about me. I’ve got a job to do. That’s the only thing I’m focused on. I’ve taken a solemn oath on my holy book. I know what’s important. And getting this right for the country is the most important thing.’

There aren’t many politicians today who seek to reassure you that they’ll deliver by telling you about the oath they’ve sworn on the Quran, but Mahmood, who is the only Muslim in the cabinet, is refreshingly candid about her beliefs. ‘It’s the absolute core of my life,’ she says. ‘If you look around my office, you’ll see quite a lot of references to my faith. It grounds me in my life, and it’s where I draw my sense of duty and public service from.

‘My understanding of Islam, how I have practised Islam my whole life, has been about viewing life as a gift from God, but it’s also a test from God. The things I have been blessed with and privileged to have like a great education. Being British, being in this country, having the freedoms that I have there, it’s a test. I have to earn it and prove I used it for good and show that I’m worthy of it. That is what drives me in public service.’

It isn’t just on prison and sentencing reform that Mahmood will face opposition. She’s also determined radically to change how the justice system operates. The situation in the courts is, if anything, more dysfunctional than our prisons. ‘One of the horror discoveries when I came into office was that even [when we’re] running the system at total maximum capacity, the backlog still goes up,’ she says. ‘And that’s because the sheer demand coming into the system is huge.’

So in order to tackle the backlog, and ensure swift justice, she is ready to restrict the right to trial by jury, a huge shift in how British justice will be delivered. ‘We need big reform in our courts… a restriction of the sorts of cases that get a Crown Court full jury trial, make more use of the magistrates’ court – but also the possibility of an intermediate court between the magistrates and the Crown Court that can hear more cases which might be judge-only or judge-led in some way.

‘There’ll be different models, I’m sure, [that are] suggested to us. That is controversial because it means some cases that currently get heard in front of a jury won’t in future. But I think we have to re-interrogate what justice really means. And if you’re a victim today of, say, rape and you’re waiting for years to get to court, that’s no kind of justice at all. So we have to do something differently here.’

Mahmood’s belief in championing the cause of victims also gives her a particular perspective on the grooming gangs scandal: ‘There have been successful prosecutions of large numbers of these criminals, and many are currently in our prisons. On one level you could say, well, accountability is occurring because these criminals are facing the full force of the law.

‘But the way that this scandal has played out asks a bigger question, which is that you might be getting accountability and justice through the criminal justice system, [but] it doesn’t feel like proper accountability and justice for all of the victims. And that’s because there is still [an] outstanding question of why so many people maybe looked the other way, or why this wasn’t picked up and given the prominence that was needed.

‘And so that’s why justice might technically have been delivered. But there’s still a moment of reckoning to come.’

Mahmood characterises that moment of reckoning as ‘a need for truth and reconciliation’. ‘There is such visceral pain and a total shattering of trust in people who should have done a better job locally,’ she says. ‘Whether local authorities, children’s services, police officers, all sorts of people you would feel you can trust, and that trust has been fundamentally shaken, if not totally broken, in some of these places… There is that need for reckoning. I hope I’m not overstating it as truth and reconciliation, but in my mind, that’s what it feels like is needed.’

Discussion of the grooming gangs scandal has, inevitably, been overlaid by questions of culture and community. As Britain’s most high-profile Muslim politician, Mahmood appreciates how questions of identity and integration have become more salient in our politics. At the last general election, she faced a challenge from a Gaza Independent candidate running on the platform that she, and Labour, had betrayed the Muslim community. Despite reportedly being unhappy with Keir Starmer’s Gaza stance earlier on during the conflict, Mahmood is critical of political parties tailoring their positions to certain communities.

‘I think on these sorts of issues, and in all politics, you’ve got to start with the thing you believe [in] and you’ve got to do the thing you think is the right thing to do, and make an argument for that first and foremost,’ she says. ‘I think politics gets into trouble and the country gets into trouble when you start trying to tailor particular messages to different communities. I’ve always raged against that as an occasional recipient of such politics.

‘We have a principled position on the conflict in the Middle East, and we’ve got to make an argument for that and why we think that’s the right way forward. There will be people who disagree and they are entitled to in this country.

‘If you ask my constituents, they want a fair managed migration system. They think there should be rules’

‘But domestic concerns to me are just as, if not more, important than geopolitical concerns. People are entitled to vote on whatever basis they want but actually, the bread and butter of how we live our lives in our own country, how we relate to our own fellow citizens – those to me are the main issues of the day.

‘So when I’m having this kind of discussion with my constituents, my argument is by all means be motivated by other things too, but your life here matters, first and foremost. And I don’t want to see the community or large parts of the community self-segregate into what might be described as sectarian politics, because then your voice in the mainstream diminishes.’

Mahmood’s belief that policy should be shaped in the national interest rather than reflecting any sectional concern also informs her approach to immigration, where she’s uncompromisingly on the side of Keir Starmer’s tougher line. ‘I look at a community that I represent which is 70 per cent non-white,’ she says. ‘If you ask my constituents, they want a fair managed migration system. They think there should be rules. Most of them will say they came in on the basis of really quite strict rules that they followed to come to this country to work and make a life for themselves.

‘They want that sense of fairness for everybody that might come now or in the future. I just don’t know why we’ve got ourselves in a tangle talking about migration controls on the left of politics, because it’s really pretty fundamental to the way a lot of our voters think.’

Starmer’s right turn on migration has been attributed to the socially conservative Blue Labour movement within the party. ‘I have a natural affinity for the faith, flag and family element of Blue Labour,’ she tells me.

‘Blue Labour is a group of people that call for more communitarian politics, a recognition of our rights and responsibilities to each other… The politics they argue for is very rooted in the day-to-day concerns of working people across our country… If you were trying to put me in a box, you would say social, small “c” conservative.’

While Mahmood may be a social small “c” conservative, she is Labour to her core, having been brought up in the party, and is respected as a formidable grass-roots organiser. It is that secure immersion in the party’s traditions, as well as her long experience of fighting street by street for Labour, that allows her to be her own woman. So when I ask her who her political heroes or heroines are, it’s no surprise they are both notably strong women.

‘Well, I tend to go for the women that broke the mould,’ she says. ‘Who came through in tight patriarchal systems – Benazir Bhutto, Margaret Thatcher – not for the substance of their politics, but for what they represented for women and the ability to make a contribution.’

Benazir and Maggie – both, like Mahmood, Oxford graduates, both known as Iron Ladies during their time. Mahmood knows she will need her own steely resolution to survive the inevitable storms ahead.

Comments