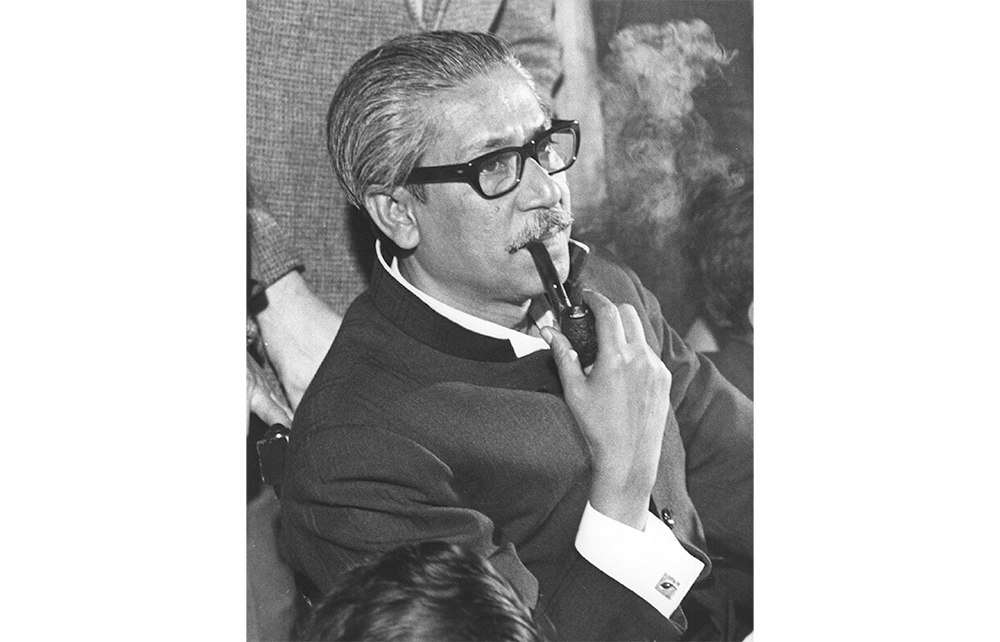

Early on Christmas morning in 1962, the Indian diplomat S.S. Banerjee heard a mysterious knock on his door in Dacca, East Pakistan. Standing outside in the darkness was a 14-year-old boy, who beckoned to him to follow, and minutes later Banerjee found himself opposite the firebrand politician Mujibur Rahman, a pipe-smoking Bengali activist who had recently transformed from a Pakistani nationalist into one of the country’s fiercest critics.

For the next hour, the two men engaged in small talk, with Banerjee growing increasingly mystified as to why he had been summoned. Then, just as he was about to go home, he was handed a small envelope intended for the Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Rahman explained that it contained a plan to break East Pakistan away from West Pakistan and establish a new ‘sovereign independent homeland’ called Bangladesh. All he needed was India’s help.

Meticulously researched, Avinash Paliwal’s India’s Near East offers a detailed history of India’s intelligence services and the country’s attempts to influence the politics of its neighbours. The cast is phenomenal, from the reclusive Indian spymaster R.N. Kao to Angami Zapu Phizo, the partially paralysed former Bible salesman who kick-started a decades-long proxy war between India and Pakistan. Many of the events described remain enormously controversial, but, armed with a slew of intelligence files, Paliwal tells a tale of espionage worthy of Ben Macintyre.

The book opens in April 1949, two years after India, Pakistan and Burma gained independence from Britain, when all three countries were racked by refugee crises and roaming militias. India and Pakistan had just been at war over Kashmir, yet their intelligence agencies now began to co-operate with one another to prevent a communist takeover in Burma.

The operation ‘must be kept completely secret’, Nehru warned his ambassador in Burma that summer. China’s Communist party had recently emerged victorious from the country’s brutal civil war, and both India and Pakistan now feared that a similar revolution was imminent in South Asia. India was already facing a communist uprising in the countryside around Hyderabad, and ‘secret and reliable’ reports indicated that communist groups in Burma were planning to spread the revolution. Faced with a joint threat, India and Pakistan would smuggle costly military equipment into Rangoon, pulling the Burmese government back from the brink of collapse.

Surprisingly, the two countries would continue to co-operate grudgingly over the next decade. The turning point came in 1958, when democracy was replaced by military rule in Pakistan, Burma and north-east India. In the following years, India and Pakistan would begin funding their neighbours’ secessionist movements, gradually embroiling their respective borderlands in a deadly proxy war.

Perhaps Paliwal’s most important discoveries relate to the early contacts between Indian intelligence and Rahman, the founder of Bangladesh and the father of the recently deposed prime minister Sheikh Hasina. Books on the founding of Bangladesh have tended to rely on memoirs and oral histories, owing to many government files having been burnt during the 1971 Bangladeshi liberation war. Nevertheless, Paliwal has managed to trace details of early Indian intelligence on the Bangladeshi freedom movement. In one document, Nehru is even found writing to his chief minister: ‘The ultimate aim is for Eastern Pakistan to join West Bengal and the Indian Union.’

Paliwal does not linger quite long enough on 1971, the fateful year when the map of South Asia was redrawn with East Pakistan gaining independence as Bangladesh and India becoming the undisputed power in the region. But he makes up for it by the surprises he offers us – for example, the number of times that India has almost intervened militarily in Bangladesh in the five decades since its independence. The result is a cautionary tale of the long-term consequences of interventionism. In his introduction, Paliwal writes: ‘India’s Near East is less connected in 2024 than it was in 1947.’ His book convincingly explains why.

Comments