When Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s hapless roving emissary, descended on London in 1936 with orders to negotiate an Anglo-German alliance, one of his first ports of call was the elegant mansion just off Hyde Park owned by Sir Roderick Jones, chairman of the Reuters news agency, and his wife Enid Bagnold, the writer of National Velvet. Wangling an invitation to dinner was a surprisingly astute move – the parties at 29 Hyde Park Gate were legendary, usually attracting a gilded mix of aristocrats, politicians, journalists and writers, such as H.G. Wells and Vita Sackville-West – and Ribbentrop had convinced himself that by schmoozing luminaries he could persuade Britain to side with the Nazis.

It did not go well. Fellow guests were astonished as, having been told that a servant could be summoned by ‘pushing a button’, Ribbentrop wilfully misinterpreted this as ‘pushing a bottom’ and dissolved into protracted gusts of loud laughter, perhaps confirming the German reputation for humour. It was the first of many gaffes that left the British bemused (nearly knocking out King George VI with a stiff-armed fascist salute would be another) and quickly established Ribbentrop’s reputation as buffoon. But there was also a more sinister coda: the day after the party, the well-liked German ambassador and anti-Nazi critic Leopold von Hoesch, who had also attended, died of a heart attack aged only 54. Ribbentrop immediately took his place. Had Hoesch, some wondered, been poisoned?

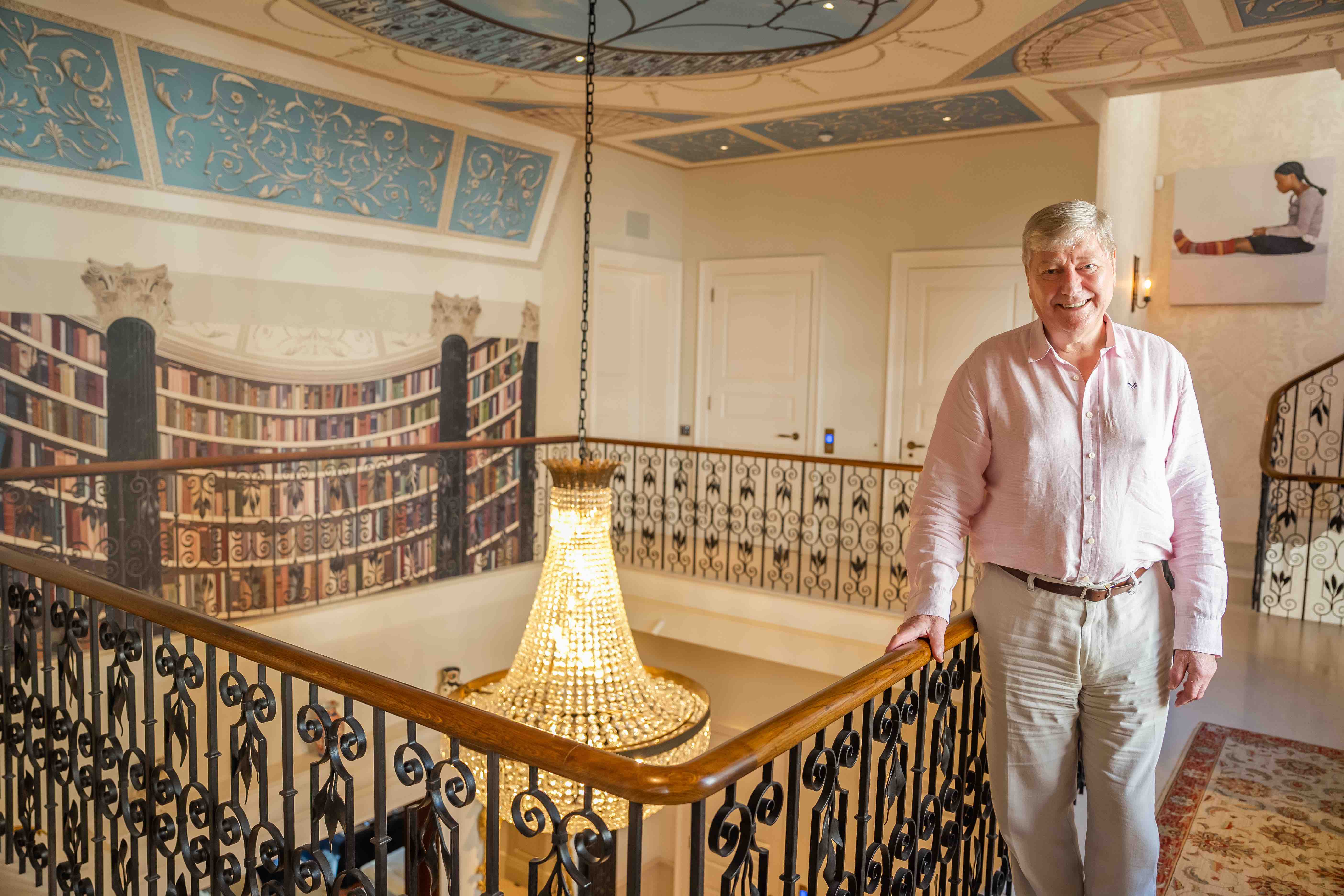

The story is told with a wicked relish by Hamish Ogston CBE, the entrepreneur and philanthropist who has spent five years and several millions restoring 29 Hyde Park Gate, a house that probably should be covered in blue plaques until indigo. Next door is the former home of Winston Churchill, where he died, while down the road lived Virginia Woolf, Jacob Epstein and Robert Baden-Powell, all of whom may have visited no. 29 at some point. It is the sort of street that has embassies.

But Monmouth House itself was in need of restoration when Ogston bought it. Built in the 1840s, with a coach house added 20 years later, the property had passed through many hands. William Heathcote, the first owner, gave way to Sir Henry and Lady Elisabeth Babington-Smith, daughter of the Viceroy of India, between 1894 and 1899. In 1927 the house was bought by Sir Roderick, who commissioned Sir Edwin Lutyens, architect of the Cenotaph, Castle Drogo and New Delhi, to transform it. Lutyens unified the main house and coach house, creating a huge drawing room and ballroom on the ground floor for entertaining and the occasional after-dinner boxing match. Perhaps predictably he won the contract to design the substantial Reuters and Press Association building on Fleet Street in 1934.

Yet the house was divided again after the war, with one half becoming the official residence of the Bulgarian ambassador in 1974 and the former coach house becoming flats. The Lutyens interiors were destroyed, with only a few panels left to guide the future reconstruction.

Enter Ogston, founder of the CPP insurance company in York and a charitable trust that supports the arts and crafts, notably heritage-related ones such as stonemasonry. ‘I’d been looking for a London address for some time and eventually Monmouth House came up. It had everything I needed, so I decided to pay an exorbitant price for it,’ Ogston jokes. He commissioned Chris Mitchell, of Mitchell Berry Architects, to turn what was formerly the coach house into a contemporary London residence and a fitting showcase for what has got to be one of the most impressive art collections in private hands in Britain today, featuring landscapes by Pissarro and Sisley, the only painting of York by Turner, and huge canvasses by Chagall and Picasso, alongside a Magritte valued at £3.5 million.

Unsurprisingly, there is more than a passing nod to Lutyens in the redesign of the £14 million property, not least the creation of a spectacular double-height entrance hall with a grand cantilevered staircase, by stonemason Ian Knapper of Staffordshire, and a handmade metal balustrade forged by Michael Jacques of Oxfordshire. Extraordinary scagliola pilasters and plasterwork by Hayles and Howe, of Devon, are exceeded only in beauty by the trompe l’oeil ceiling which appears to offer a view to a dome and azure skies beyond, while the trompe l’oeil on the south wall, also by Fiona Sutcliffe, from London, seems to lead to a library of bursting bookshelves in a nod to Robert Adam, the Georgian master. The adjacent drawing and dining room, with huge windows offering views of the garden behind, are perhaps more contemporary and show the art to striking effect, while upstairs is a private screening room and sumptuous bedrooms.

So far, so domestic, but Ogston, 74, has made headlines recently by revealing that he has refused to leave any part of his substantial wealth, in the hundreds of millions, to his three children. Packed off to join the Norwegian merchant navy at the age of 18 with £50 by his father, a dentist, he travelled the world before returning to study at Manchester University and embarking on a successful business career. He wants his children to follow suit. So upon his death, 29 Hyde Park Gate will pass to the Hamish Ogston Foundation, which is already doing so much to support apprentices in stone masonry, carpentry and ironworking and similar heritage trades at places such as Wentworth Woodhouse, the enormous Grade I-listed country house near Rotherham in Yorkshire. It is a gesture of generosity that turns the restoration of this storied address into an act of national significance.

‘The use of the property for the foundation is already helpful in that when people come here it is not your normal house, it is something rather different and will stick in their minds,’ Ogston says. ‘But when I do die, I’ve bequeathed the freehold to the foundation. And we’re now in talks with a bank to get them to lend against that as collateral so I can have some or most of the money given away during my lifetime. I’m just trying to be the best philanthropist I can be.’

Comments