Labour’s proposal to impose VAT on private school fees will, we are often warned, lead to state schools becoming overloaded as parents withdraw their children from the independent sector and try to find alternative arrangements. That may turn out to be true in some areas in the short term, but in the longer term there is a different problem facing the state and independent sectors alike: a falling population of school-age children. It isn’t excessive class sizes which threaten to be an issue so much as shrinking classes, leading to school closures and amalgamations with other institutions.

London classrooms appear to be emptying – in 2022, 15.5 per cent of primary school places were unfilled

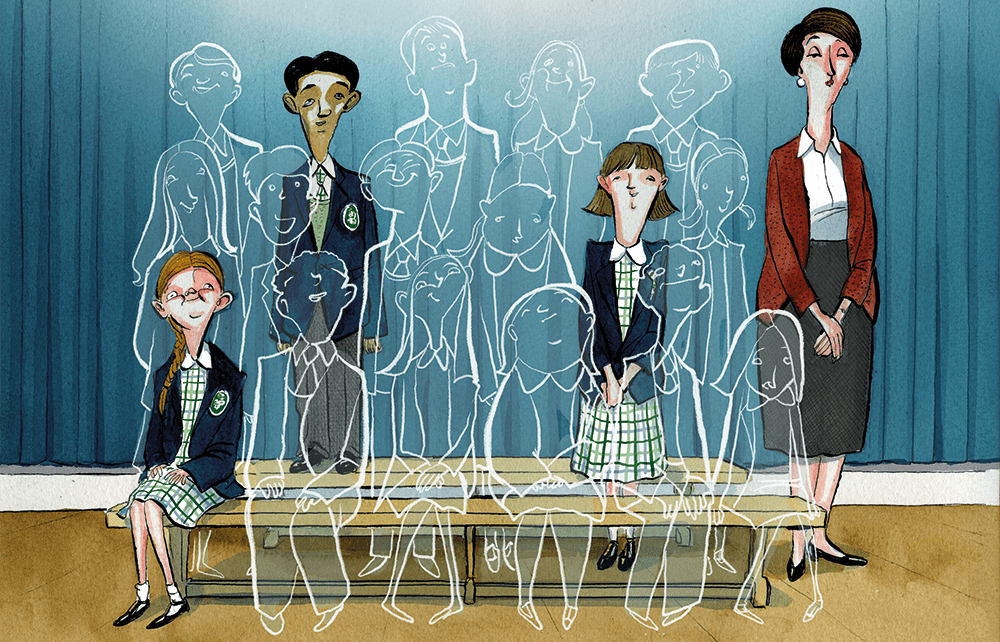

For nursery and primary schools in England, pupil numbers peaked in 2019. By 2028, according to the government’s projections, pupil numbers will fall a further 207,000 to 4.36 million. That is equivalent to 100 Grange Hills’ worth of pupils simply evaporating over the next four years.

In some areas the fall will be especially precipitous: Lambeth, Hillingdon and Ealing are all expected to lose 15 per cent of their pupils over the next three years. For secondary schools, the demographic trends inevitably follow a few years later. Numbers are expected to be at their lowest in 2026/27.

Much has been written about the deleterious economic effects of an ageing population, as fewer working-age people have to support a still-growing population of retired people – whose state pensions are paid out of current tax revenues.

But for schools, the problem of a shrinking population is arriving much sooner. The background to this is falling birth rates throughout the developed world, and increasingly in developing countries too. Of around 40 countries deemed by the World Bank to be ‘developed’, only one has a Total Fertility Rate – the average number of children born to women during their child-bearing years – above the replacement rate of 2.1. That is Israel, on 2.82. In Britain it is 1.87.

That overall figure masks the more detailed picture: that the fertility rate is only holding up thanks to a far higher fertility rate among the migrant population. In 2022, 30.3 per cent of births were to mothers who themselves were born outside the UK.

What does this mean for schools? State schools have already seen some closures: the number in London fell by a net 11 between 2020 and 2022, from 2,561 to 2,550. Among those lost are Archbishop Tenison’s School and St Martin-in-the-Fields High School for Girls, both ancient foundations which were run as state academies in their last years. In Lambeth, where both schools were based, there is an additional factor impacting on school rolls: the redevelopment of council estates which had significant numbers of family-sized homes; many of the higher-density replacement flats have one or two bedrooms.

London classrooms appear to be emptying – in 2022, 15.5 per cent of primary school places were unfilled. There are grants available to keep schools with falling rolls open, but that money is only going to go so far. Not every school will be spared like Milburn School in Cumbria, which had 32 pupils on its roll in 2001 but when inspected again in 2020 had just seven, taught by a single teacher. It was then reported to be the smallest school in England, but has evaded closure thanks to its remote location. No urban school is going to be allowed to shrink to that size before the fabled men from the ministry flog off its site to developers.

Nor, indeed, do all remote schools survive the axe. The Skerries School, which served a small group of islands off the Shetlands, made Milburn School look crowded, with a roll down to just three pupils before the Shetland Islands Council called time this summer. From the autumn term pupils will be transferred to a school in Lerwick, the metropolis of the Shetlands. The school has twice been mothballed before, once when it had precisely zero pupils.

Interestingly, the independent sector has avoided the demographic crunch. Apart from a small dip around the ages of seven and eight (the number of seven-year-olds has fallen from 27,424 in 2019 to 26,861 this year), primary, prep and pre-prep schools affiliated to the Independent Schools Council (ISC) have managed to retain stable rolls over the past five years. From age 11 upwards there have been substantial gains in rolls: the number of 15-year-olds at ISC schools grew from 47,740 in 2019 to 53,541 last year. Even so, not all have survived. Falling rolls led to the announcement by Alton School, Hampshire, that it is to close after 86 years.

Given that they only educate 6 per cent of children, the fortunes of independent schools are not exposed so directly to the birth rate as are those of state schools. An independent school can find itself in trouble in spite of a baby boom if it fails to persuade enough parents it is worth spending money on private education over the free-at-the-point-of-delivery state option. Conversely, independent schools can still flourish against a backdrop of falling births if they can grab a larger share of the overall education market.

If all else fails, they have the option of giving themselves up to the state sector. It worked for Liverpool College, according to headmaster Hans van Mourik Broekman, who helped convert the school into a state academy 11 years ago. The increase in pupil numbers, he says, enabled it to start teaching Latin – which it hadn’t done before – and to set up an orchestra.

Falling birth rates are certainly going to claim some casualties among Britain’s schools, state and independent sectors alike. But the victims will not necessarily be the ones you might expect. So long as there is still someone breeding in the neighbourhood, there may yet be ways to keep your school’s doors open.

Comments