There is no such thing as a bad friend. The societal expectations and collective imagination of what friendship should look like have, over the past century, set unrealistic expectations, meaning we are all doomed at some point to fail as friends. At least this is what the cultural historian Tiffany Watt Smith argues in her new book.

Bad Friend is elegantly written as part memoir, part history, citing multifarious sources, from 12th-century Paris to the American sitcom Friends. The author weaves in her own experiences of female friendships, candid that her research for the book made her reassess the formative and transformative relationships she has cultivated in her life.

Reading the book forced my own recollection and reconsideration of friendships. I remember in my emotionally charged early teens decorating my friend’s arm in coloured gel pen, honoured to be doing so. Watt Smith notes this as a sort of innocent ‘girl crush’, commonplace but endorsed in boarding schools from the late 19th century as a rite of passage: ‘The relationships [would] teach the tender-hearted and compassionate ways necessary for successful marriage and motherhood. Stories for girls encouraged romantic friendships.’ As Watt Smith demonstrates, this is clear in the Malory Towers series, in which Enid Blyton portrays her character Mary Lou as a boarding school girl with a crush on the cooler Darrell. ‘She trails around after Darrell, yearning for her company, performing little acts of service.’

Unlike institutionalised relationships such as marriage, women’s friendships are frustratingly elusive to a historian seeking to recover them and Watt Smith acknowledges the difficulties she encountered. Casting her net for original ways to access emotions in the record, she is inspired by the black feminist historian Saidiya Hartman, who developed ‘critical fabulation’. This was a method that allowed her ‘to foreground the gaps in our historical knowledge and ask questions about a historical actor’s motivations without necessarily knowing how to answer them’.

This idea is crucial to Watt Smith as she recovers the story of two female inmates at the Auburn Correctional Facility in New York in the early 20th century: Madeline, an undercover agent reporting on conditions in the prison, and Minerva, a black woman, ‘whose job it was to go from cell to cell each evening with the water jug’. The two became friends, with Madeline trying to extract information about Minerva’s experience. Watt Smith is drawn to the imbalance of power in this friendship, told from Madeline’s perspective as ‘the one ray of comfort’, but never told from Minerva’s. ‘Did Madeline assume… that as a black woman, Minerva was there to accommodate and protect her and do her bidding?’

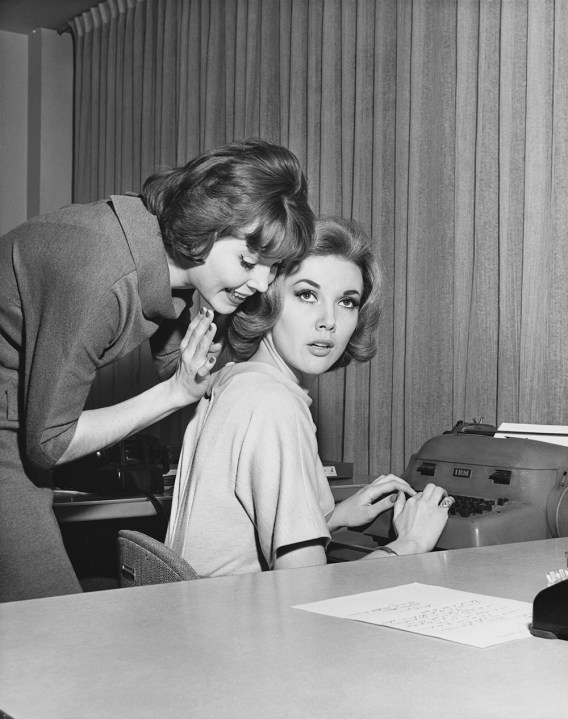

The innocent ‘girl crush’ was endorsed in late-19th-century boarding schools as a rite of passage

One of the least documented areas of female experience and friendship is in the domestic sphere; yet historically this was a space that not only necessitated female friendships but nourished them. In the second world war ‘there were mothers in bustling kitchens… and children who wandered in and out of people’s homes. These women helped one another, providing endless emotional support around kitchen tables, childcare, food and even money’.

The modern experience looks very different. I personally balked at the idea of NCT (National Childbirth Trust) classes. Or, as my friend put it, ‘the most expensive phone book you will ever have’. I saw it as Watt Smith does – ‘a cliché’. I feared the ‘mum group’, but ‘given the desperate loneliness of motherhood in an age of the private nuclear family’, it was essential.

Watt Smith marks the popularity of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which painted a bleak picture of home life in the 1960s as a moment when women began to talk about the drudgery of domesticity, calling it ‘the problem’. ‘They wept over those foaming dishpans. They raged internally.’ But on the other side of suburbia’s tracks a very different scene unfurled. Child-sharing was normalised and ritualised in black communities known as the Flats across New York and Chicago: ‘Close female kinsmen in the Flats do not expect a single person, the natural mother, to carry out by herself all of the behaviour patterns which motherhood entails.’

Throughout the book we see women naturally communing for support and safety. In 12th-century Europe a group of single women lived together in a non-cloistered community called the Beguines. Watt Smith examines one crucial source for medieval women in trying to understand their closeness – their wills. She found frequent mentions of a socia, a compagnesse, a friend.

The book is a brilliant ode to the necessity and complexity of female friendship but shatters the rose-tinted view of what it should look like by showing friendships that are tender, raw, angry and imperfect. We also see the way women choose to commune together, be they in ‘covens’ or ‘cliques’. With my catalogue of unanswered WhatsApp messages, I breathe a sigh of relief when Watt Smith blasts the ideal: ‘The perfect friend seems too brittle; how could she not shatter?’

Comments