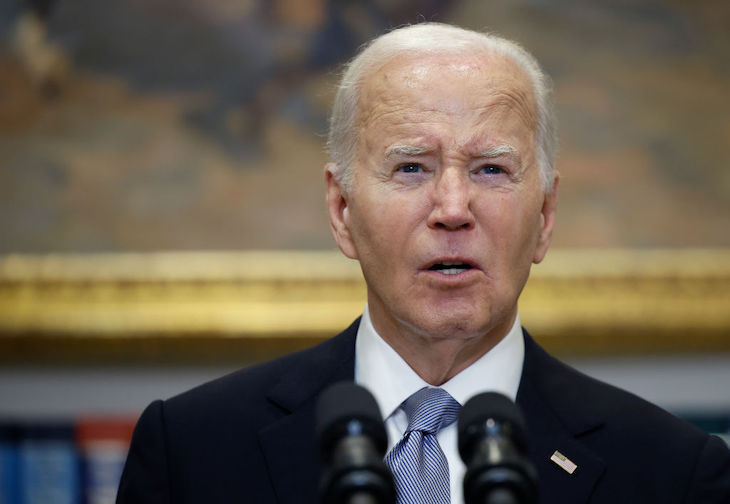

One waspish – but not entirely inaccurate – Russian media assessment of the first US presidential debate was that it was ‘a reality show about the lives of pensioners.’ They ought to know, as Russia’s own history has highlighted the dangers of gerontocracy.

When the Bolshevik revolutionaries who had just seized power formed their ruling Politburo in 1917, the only member who was more than 40 years old was their leader, Lenin, at 47. By 1981, the average age was 69. As for the actual leaders, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev died at the age of 75 in 1982. His successor, Yuri Andropov, was a relative stripling, dying in 1984 at 69, to be followed by Konstantin Chernenko, who died in 1985 at 73.

In part this was because in the Soviet Union – as in Vladimir Putin’s Russia – power is all. An individual’s security, status and prosperity are all products of their position, and to retire was to risk being marginalised and even persecuted, so successive General Secretaries clung to it until it fell from their dead fingers. In this respect, as in so many other, Mikhail Gorbachev was the honourable exception.

The implications of gerontocracy were serious. Ageing rulers were typically out of touch with their own country, let alone developments in the world around them. In his final years, Brezhnev was notoriously unmoored, so much so that he became a figure of fun. One joke went that he began his speech opening the 1980 Moscow Olympics with ‘O. O. O. O. O. O.’ until one of his aides quietly told him that the six Os at the top of the page were actually the rings of the Olympic logo, not part of his address.

More seriously, he and his fellow septuagenarians had trouble often responding to fast-moving crises, repeatedly trying to force them into the patterns of past events (while discussing the proposed invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Brezhnev apparently several times referred to it as ‘Czechoslovakia’ – which he had invaded in 1968). Alternatively, they lacked the stamina such a demanding job required. Andropov, for example, held his mental acuity to the end, but spent most of his brief tenure ruling from a hospital bed, hooked up to dialysis.

Ageing leaders are not only often hard-pressed to adapt to new ideas and introduce necessary changes, they are also vulnerable precisely to being manipulated by their allies, advisers and aides. Perhaps without the energy or ability to go outside these circles, they are also presented with bewildering new ideas and potential threats they rely on others to interpret. Today it may be the technobabble of AI and nanotechnology, but to the Soviet gerontocrats it was the information revolution and Ronald Reagan’s ultimately-impracticable but dramatic-sounding ‘Star Wars’ antimissile project.

Arguably, they also have rather different political horizons, too. Why think about the next twenty years if you suspect you’ll be hard pressed to live another five? Many of the systemic problems that brought down the USSR – a sclerotic planned economy, excessive defence spending, endemic corruption, ideological calcification – became quite so intractable because they had been put off so long.

Vladimir Putin is ‘just’ 71, and while his government looks very different from its Soviet predecessors – prime minister Mikhail Mishustin is 58 – there is more than a touch of gerontocracy where it counts. The cabinet is, after all, not the dominant body in his increasingly monarchical system, but rather largely the technocrats whose role is to execute instead of formulate policy. If one looks at the people who really count in Putin’s court or in presenting it to the outside world, a different picture emerges.

History thus reminds us of some of the dangers of gerontocracy

The man who has done the most to shape Putin’s paranoid view of the outside world, former Security Council secretary and now presidential aide Nikolai Patrushev, is 73. Although he has very little role in shaping foreign policy, its face is the 74-year-old Sergei Lavrov. Security chief Alexander Bortnikov is 72, National Guard head Viktor Zolotov is 70 and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov is 69.

Already, there have been indications that this is affecting policy. These figures are all examples of ‘homo sovieticus’, whose ideas – including their implacable suspicion of the West and imperial assumptions – were shaped by a system long since dead. Their horizons are also closer than the rest of the elites’. Whereas Putin seems willing to make whatever concessions are necessary to Beijing in order to retain its support in his war in Ukraine, for example, this is disturbing many of the 50- and 60-year olds within the government, who, when they finally get their chance for power, do not want to find themselves ruling a Russia that has become a Chinese vassal state.

History thus reminds us of some of the dangers of gerontocracy. Still, at least Putin is only 71, not 78 – or 81.

Comments