Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades is one of those operas that under-promises on paper but over-delivers on stage. It’s hard to summarise the plot in a way that makes it sound theatrical, even if you’ve read Pushkin’s novella, and I’ve never found a recording that really hits the spot. And yet, time and again, in the theatre: wham! It goes up like a petrol bomb. With a good production and performers, Tchaikovsky hurls you out at the far end feeling almost hungover – head swimming, and wondering where those three hours went.

The cast and staging at Garsington are very, very good. True, you’d expect great things from any production that can afford to cast Roderick Williams (Yeletsky) and Robert Hayward (Tomsky) in what are essentially supporting roles, and the director is Jack Furness, who at his best (like his Garsington Rusalka in 2022) has been responsible for some of the most compelling British opera of the past decade. Furness is on top form here, delivering multilayered storytelling underpinned by subtle characterisation. He has an eye for spectacle, as well as the tiny details that speaks volumes.

The Philharmonia is the orchestra, and while they haven’t always brought their A-game to Garsington, they’ve typically responded well to the festival’s artistic director Douglas Boyd. Good news: he’s conducting The Queen of Spades, and from the first notes – the clarinet’s question in the silence; that hot-breathed surge of string tone – it’s as tense as a guilty conscience. Cue baleful brass chords, aching woodwinds and those quiet, nagging ostinatos which mean that like the opera’s anti-hero Herman (Aaron Cawley), we never really get to relax.

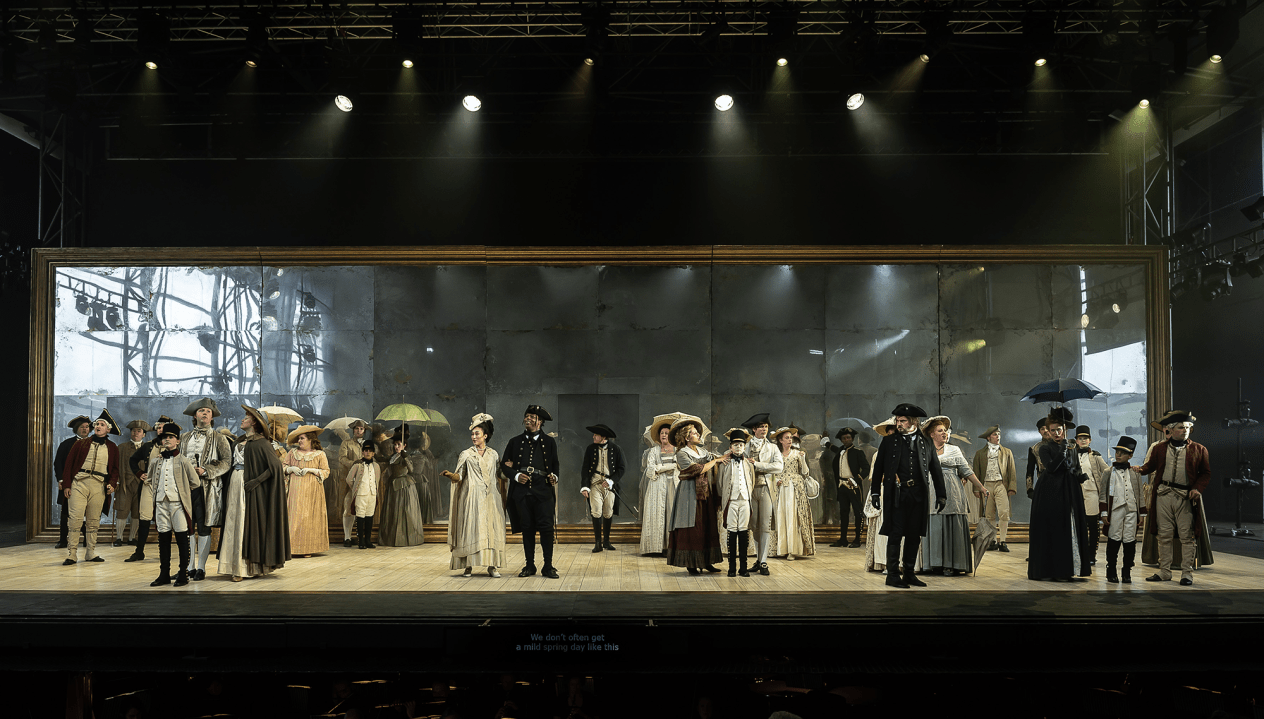

Cawley makes an unusually complex Herman, dressed in black against the pleasant pastels of the rest of the cast (Furness has retained the original 18th-century setting, which is impressive in itself). In his red-blooded early exchanges with Hayward I worried that Cawley might have peaked too soon; both singers sounded larger than life. But that presupposes that there’s only one possible direction of travel, and part of the fascination of Herman’s descent into madness is the way Furness makes his behaviour keep us guessing while Cawley’s singing – real vocal acting – hints at inner decay.

So that virile, bronzed tenor grows hollow and tight, and one of the most chilling moments occurs at the climax of his love duet with Lisa (Laura Wilde), when they come together in what ought to be bliss, but end up closer to hysteria. Wilde’s Lisa is very far from innocent as she inches towards complicity with Herman, and there’s steel as well as pathos in her singing. Furness handles these performers superbly, just as he deploys Williams’s natural warmth and Hayward’s vocal grandeur to throw Herman’s final collapse into even bolder relief. The elderly Countess – so often a desiccated grotesque – is played and sung by Diana Montague as a vital, flesh-and-blood woman.

It’s almost impossible to convey the impact of this particular opera in words. Go and see it

In short it’s all a lot less simple, and therefore a lot more exciting, than it has to be. Beautiful to look at, too, with Tom Piper’s designs (a maze of tarnished mirrors) suggesting the ego and id of Tsarist high society. Smoky vignettes of card games and soirées swing around to reveal seamy backstage goings-on, or Herman’s garret with its revolutionary tricolore (our hero, apparently, has been radicalised on the quiet). This Queen of Spades is full of touches like that; proof that thrilling musical and dramatic values can serve rich and intelligent storytelling. But again, it’s almost impossible to convey the impact of this particular opera in words. Go and see it.

Longborough Festival Opera, meanwhile, has opened the season with an even more daring gamble – the UK première of Avner Dorman’s Wahnfried, an opera about the unsavoury relationship between Cosima Wagner and the Europhile racial supremacist Houston Stewart Chamberlain. They’ve spared no effort, casting Mark Le Brocq and Susan Bullock in the lead roles – two exceptional artists, each giving a masterclass in imperious unlikability. It’s directed with exuberant, tumbling theatricality by the Festival’s artistic director Polly Graham, who fills the stage (a David Lynch-inspired Red Room) with acrobats and kinky Pierrots. The ghost of Wagner appears as an imp in a lime-green codpiece.

Justin Brown – who conducted the opera’s world première in Karlsrühe in 2016 – is in the pit and the LFO orchestra romps all over Dorman’s hyperactive, Shostakovichy score. The pity is that all this talent is squandered on such a hectoring, cartoonish drama: a libretto that never shows when it can tell, and characters with little nuance or inner life. The cast is tireless, but the overall sensation is a bit like being stuck in a car with a mouthy teenager who has skim-read German Nationalism for Dummies. Still, it does include the line ‘Houston, we have a problem’, so fair play there.

Comments