I like to think of myself as a latter-day Mother Shipton. I may not live in a cave in the north of Yorkshire, but I do occasionally dabble in prophecy. And, like Mother Shipton, I am accurate approximately roughly one per cent of the time.

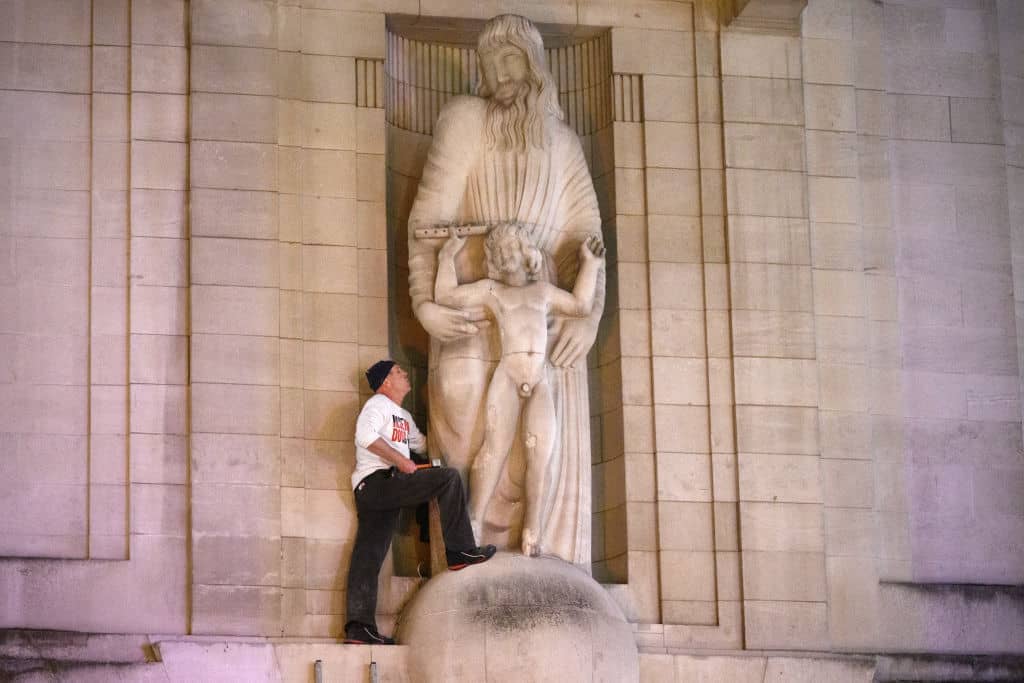

And I can prove it. In a diary piece for the Spectator in June 2020, I wrote the following: ‘Is it really any great leap to suppose that the same activists who would see a statue of Mahatma Gandhi toppled for his ‘problematic’ views might not wish the same fate on Eric Gill’s sculpture of Prospero and Ariel on the facade of the BBC’s Broadcasting House?’ This week, a man fulfilled my prediction by climbing a ladder and attacking Gill’s work with a hammer.

If you sanction vandalism for your own particular cause, you shouldn’t be surprised when the same tactics are deployed elsewhere

In truth, it didn’t take any great powers of divination to see this one coming. In his diaries, Gill admitted to sexual relations with his sisters and to molesting two of his daughters and the family dog. Had this information been public knowledge in 1932, the sculpture would doubtless never have been commissioned. And given the vogue for statue-toppling in the current climate, how could Prospero and Ariel possibly survive?

Inevitably, many commentators are making the connection between this act of vandalism and the recent acquittal of the ‘Colston Four’. Although the verdict does not necessarily set a legal precedent, it could be seen as a green light to others who might feel inclined to deface public monuments of which they disapprove. Hannah Arendt wrote of the self-defeating nature of political violence, and how ‘the means used to achieve political goals are more often than not of greater relevance to the future world than the intended goals.’ If you sanction vandalism for your own particular cause, you shouldn’t be surprised when the same tactics are deployed elsewhere.

The comparison with Colston has its limitations. It was not the artist John Cassidy that provoked the ire of protesters in Bristol, but the figure he had depicted. In the case of Gill, the sculpture of Prospero and Ariel was attacked as a statement against the sins of its creator. Unless, of course, our hammer-wielding art critic was a social justice activist who was upset about the colonial implications of The Tempest. Let’s face it, this isn’t beyond the realms of plausibility.

Of course, this all boils down to the everlasting debate over whether or not we can separate the art from the artist. Gill’s crimes were unforgivable, but the statue is blameless. Are we to suppose that a work of art is somehow magically invested with the soul of its maker? I think not, and I worry that in taking this line we are legitimising future acts of vandalism against some of our most important cultural artefacts.

To be a great artist takes a kind of mania, an unrelenting obsession to see one’s dreams and visions brought to life. Not all artists are morally repugnant, but many of the most important ones throughout history have been. So while it would be a public duty to see Gill on trial for his crimes were he alive today, we achieve nothing but cultural immiseration by destroying the beautiful works he left behind.

It is said that Caravaggio murdered a man while attempting to castrate him. Should we therefore hurl his Bacchus and his Judith Beheading Holofernes into the incinerator? For over a hundred years it was believed that Brahms strangled cats in order to replicate their dying cries in his symphonies. If this had been accurate, would we be justified in consigning his music to the memory hole? And what of the rumours that Michelangelo crucified a model in order to precisely reproduce the muscular contortions and agony of Christ on the cross? Even if this turned out to be true, only a philistine would delight in seeing the Sistine Chapel given a new lick of paint.

For all my powers of prophecy, there is no way I can predict which currently acceptable modes of behaviour will be condemned by future generations. If we tolerate iconoclastic demolition on the basis of subjective judgment, we establish a precedent that we may well live to regret. One wonders how the bronze bust of Karl Marx over his grave in Highgate Cemetery will fare, given that his political philosophy and his casual use of racial slurs makes him a potential target for both the right and the left.

It is of course entirely understandable that the crimes of Eric Gill mean that some of us cannot appreciate his work without a gnawing sense of unease. But this is a subjective feeling, not a mandate to destroy art. Nobody who appreciates Gill’s work is thereby excusing paedophilia, any more than those of us who object to mobs tearing down statues of slave-traders are endorsing human trafficking. It is tempting to reduce such issues to simplistic binaries of Good versus Evil, or those who are on the ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ side of history, but this is an infantile approach to matters that require nuance. It is far better, surely, to have these difficult conversations without the aid of hammers.

Comments