Many years ago I wrote a book called Dreams and Doorways, a collection of interviews with well-known people – writers, actors, politicians, sports personalities – about their childhood. I wanted to find out how their early experiences helped to turn them into the high-achieving adults they later became. And in almost every case, some kind of deprivation or anguish or obstacle was a key factor; they’d been motivated by a determination to overcome adversity.

My days were a little less happy. My mother didn’t believe in the permissive child-rearing policy of liberal American moms

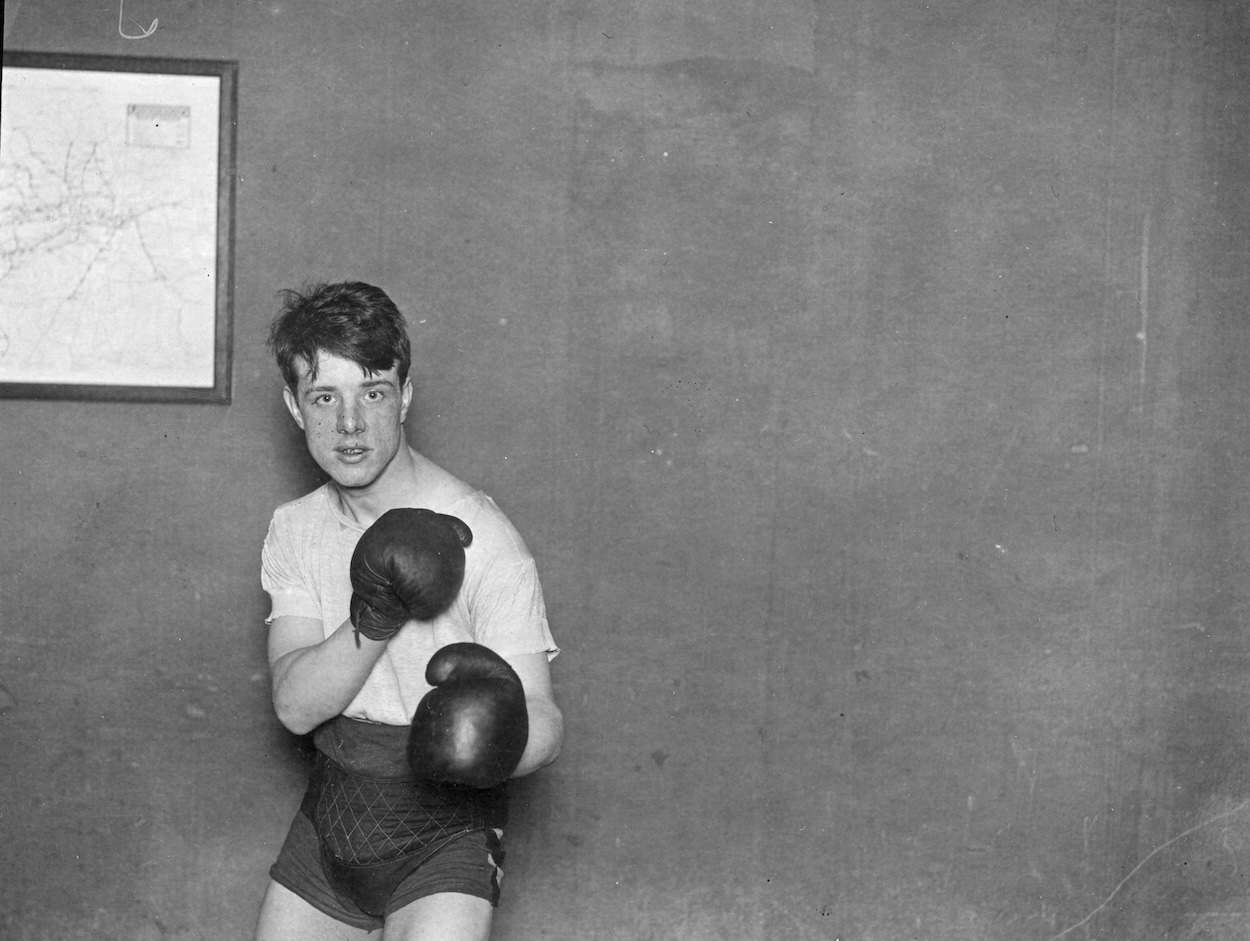

For boxing champ Henry Cooper, it was extreme, ‘bread-and-dripping’ poverty in South London. For Olympic javelin thrower Fatima Whitbread, it was being abandoned as a baby and growing up in a loveless children’s home. Actress Susan Hampshire had suffered from crippling dyslexia, and politician Edwina Currie battled against the stifling orthodoxy of her provincial Jewish upbringing. Champion weightlifter Dave Prowse, who went on to play Darth Vader in Star Wars, was stricken with tuberculosis of the leg at the age of 13, resulting in a year’s stay in hospital followed by three years wearing a calliper.

Bestselling author Douglas Adams had a disturbed childhood as a result of his parents’ vitriolic marriage and consequent divorce. As divorce was uncommon and stigmatised back in the 1950s, it set him apart from others. He was further distressed by growing so much taller than his peers, as well as by being left-handed. ‘I had a sense of the world having been designed for everyone else but me,’ he said, ‘so I was plagued by worries and self-doubt.’

My father, Péter Halász, was a writer too. By his late teens, he had already published scores of adventure novellas. His first full-length novel came out when he was 20 and established his name in Hungary. He once told me that he wrote out of loneliness. An only child, his parents had separated when he was five; he was shunted around and for a while lived in a children’s home where his Jewish background left him open to anti-Semitism. Inventing tales, some of them set in the Wild West or foggy streets of London, set his imagination soaring and peopled his solitary world with exciting characters. Writing saved him, he said.

When I reflect on my own childhood and adolescence, I sometimes wonder whether I would have had a literary career at all if I’d had the sort of easygoing upbringing enjoyed by my contemporaries in the America of the 1960s. Their lives were full of Saturday night dances and pyjama parties and smoochy dates at drive-in movies – the stuff of that TV sitcom Happy Days. My days were a little less happy. My mother didn’t believe in the permissive child-rearing policy of liberal American moms, but rather in the traditional, strict method she herself had been subjected to in rural Hungary in the early decades of the 20th century.

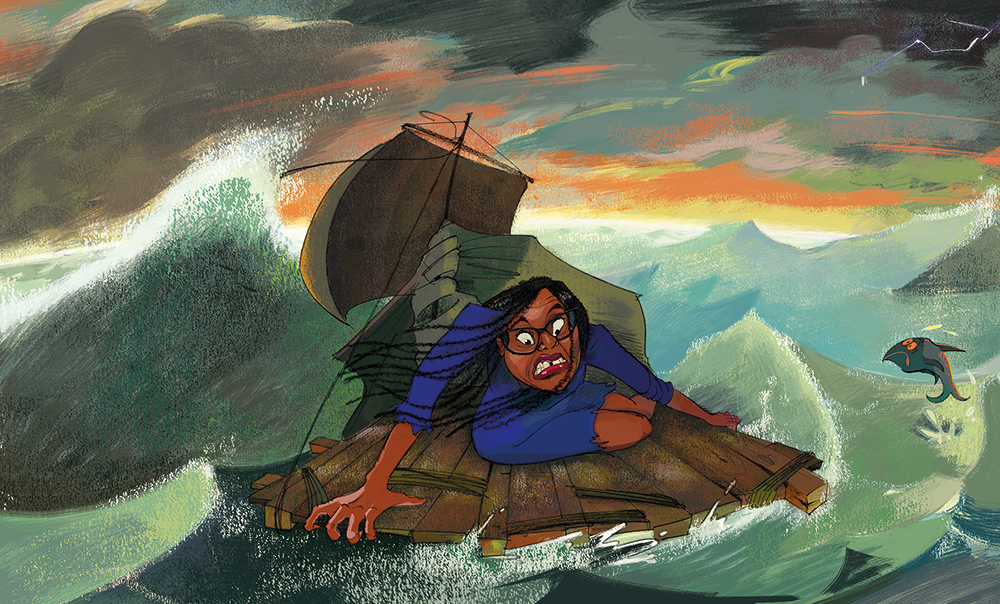

You can imagine how this alienated me from the mainstream culture around me. I yearned to be gadding about with my pals, footloose and fancy-free. Instead, I would be holed up in my room, pouring my troubles into poetry and other secret scribblings. Like my father, I turned to writing as an escape from painful reality, a kind of self-led therapy. Eventually, it evolved from a habit to a vocation.

In later years, my complex, atypical and uneasy family background provided me with some good material to write about in articles and books. The truth is that a troubled childhood generally makes for a better story than a carefree one. As it turned out, the mother who had given me so much grief as a kid was the same woman who gave me my most intriguing subject as an author, when I wrote about her heroic exploits in Nazi-occupied Budapest. It turned out that she had always been a forceful, uncompromising character.

I guess the big question is whether early unhappiness is worth it in the end, as it can be forged into something positive and provide a galvanising spur to achievement. Looking back from my present perspective, I would say yes, it’s worth it. My Swinging Sixties were pretty rubbish, but it was a long time ago and doesn’t matter anymore. My 15-year-old self would doubtless answer very differently. After all, I had just run away (for two days), was miserably trudging back home to face the music, and at that point, I would have given anything to be a character in Happy Days.

Comments