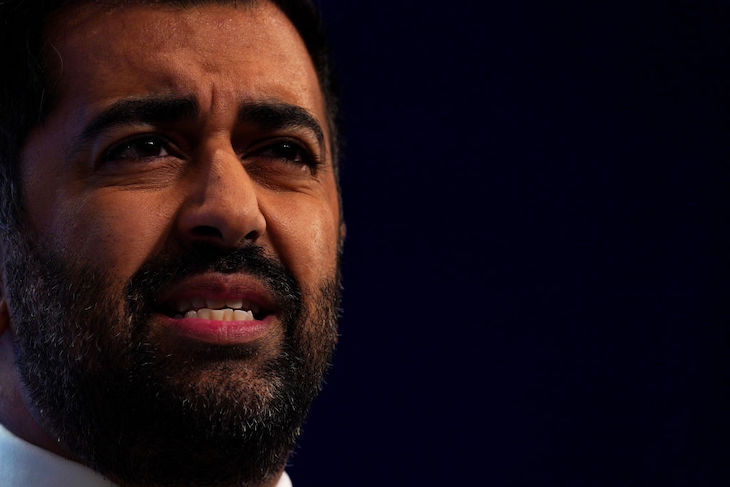

There have been extraordinary goings on at Holyrood this week – and I don’t mean more iPad-on-holiday revelations or sleazy claims two SNP politicians broke lockdown rules while having an affair. I’m referring to evidence put to the Scottish parliament’s equalities, human rights and civil justice committee on the Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill, which aims to change the way legal services are regulated in Scotland.

The profession is regulated by the Law Society of Scotland, the Faculty of Advocates and the Association of Construction Attorneys, under the general supervision of the Lord President, Scotland’s most senior judge who presides over the Court of Session. The bill would radically reform this arrangement. Scotland’s senior judiciary has summarised it as the government proposing to ‘take into its own hands powers to control lawyers; remove aspects of the Court of Session’s oversight of the legal profession; and impose itself as a co-regulator along with the Lord President’.

In typical SNP style, the changes they have come up with attempt to introduce an element of central government control or influence where previously there was none

Ministers say the aim is ‘to provide a modern, forward-looking regulatory framework for Scotland that will best promote competition, innovation, and the public and consumer interest in an efficient, effective, and efficient legal sector’. Giving evidence at Holyrood this week, however, Scotland’s second most senior judge, Lord Justice Clerk Lady Dorrian, described the reforms as ‘constitutionally inept’, posing ‘a threat to the independence of the judiciary’.

‘Members of the judiciary rarely attend parliament to comment on proposed legislation, and the fact that we are doing so merely underlines the extent of our concern,’ Dorrian informed the committee. She went on to highlight as key concerns the removal of the Lord President and the Court of Session as the ultimate regulators of the profession, and the ‘constitutional threats’ to the independence of the judiciary and of the legal profession posed by the bill. Dorrian also said that regulation by the Lord President ‘independent from government’ ensures compliance with the separation of powers and the rule of law central to our democracy’.

Under the bill, Scottish ministers would be given direct control to change the professional obligations of lawyers, to reassign regulatory categories, to review the performance and impose sanctions on the regulator, to directly exercise power to regulate the profession, and to even set up an entirely new regulator, according to Dorrian.

And Scotland’s senior judges are not the only ones raising a red flag. The Law Society of Scotland warned in its written submission to the committee that the bill would ‘allow unprecedented levels of political control and interference over many of those who work to hold the politically powerful to account’. It says:

The bill could see the Scottish government intervene directly on the rules and structures that decide who can and cannot be a solicitor, decide the professional requirements placed upon solicitors, and decide the way in which legal firms operate. This is deeply alarming.

Going further on the risk of the state regulating law firms directly, the Society states:

We believe it is dangerous and wrong to undermine the independence of the legal profession in this way. Not only will it weaken the Scottish legal sector in what is an increasingly internationally competitive market, it will also damage the global reputation of Scotland and its justice sector. There is a real risk that autocratic regimes in other parts of the world could use Scotland as an excuse to justify similar controls on the lawyers in their own countries.

This is highly robust language from senior lawyers, and no doubt deliberately so. Is the profession simply circling the wagons to protect its cosy industry setup, or are the complaints valid? Certainly, some groups, such as UK regulatory body, the Competition and Markets Authority, have called for the establishment of a single, independent regulator on the basis that the current arrangements create the potential for conflicts of interest. And there was wide consensus before the introduction of the bill that some form of shake-up was needed.

In typical SNP style, however, the changes they have come up with attempt to introduce an element of central government control or influence where previously there was none. The nationalists have form here. When the party merged all of Scotland’s regional police forces into one Police Scotland they removed local democratic accountability via independent boards of local councillors — instead replacing them with a single Scottish Police Authority consisting of members appointed by Scottish ministers. And when the SNP reformed higher education in 2015, the Sturgeon administration tried to give ministers the power to make changes on university governing bodies and academic boards, but ultimately backed down.

On the political interference point, therefore, Scotland’s senior lawyers and judges are right to be wary. The SNP has a history of trying to aggregate power at the Holyrood level, even when it damages Scotland. Not for the first time, those who shout loudest about respecting Scottish democracy demonstrate a willingness to abuse our democratic norms and safeguards.

Comments