[audioplayer src=”http://rss.acast.com/viewfrom22/thegreatbritishkowtow/media.mp3″ title=”James Forsyth and Stephen Bush discuss the upcoming Labour party conference” startat=1650]

Listen

[/audioplayer]Five years ago this Saturday, Ed Miliband was crowned Labour leader. Three days later, he had to deliver his first conference speech in that role. It was a distinctly underwhelming address. Miliband was overshadowed by his brother, who ticked Harriet Harman off for clapping. To try to give its new leader a better start this time round, Labour decided to announce the result of its leadership contest a fortnight before the party conference.

But two weeks has been nowhere near enough time for Labour to come to terms with what has happened. The Parliamentary Labour Party is still in a state of shock about Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. One senior Labour MP fumes, ‘It’s beyond a joke, but it is now my life,’ while even Corbyn’s early backers still can’t quite believe that he has actually won and that they are now in charge.

For these reasons you won’t be able to judge Labour’s conference by the normal rules. If there is some sophisticated conference grid designed to get the party’s new message across, the shadow cabinet are not aware of it. The media’s old party conference game of ‘find the split’ will be pointless this year. Labour frontbenchers won’t bother to hide their disagreement with their leader on a whole slew of issues. One figure close to many on the front bench says, ‘We’re not living in a world where there’s collective responsibility across the piste.’ Rather, they say that shadow cabinet members have agreed to serve as long as they accept the new leader’s policy agenda in their own particular brief.

Corbyn’s conference address will not, if his leadership to date is any guide, abide by the normal rules either. His turn at the Trade Union Congress showed that he has no intention of abandoning his habit of writing his speeches as he delivers them. The result there was an address that was authentically Corbyn but that did not deliver some of the lines which had been briefed to the media. Indeed, the Tories have been pleasantly surprised at how poor a public speaker the new Labour leader is. Many of them assumed that he would be in the Tony Benn class. But Corbyn is no rhetorician.

One test of Corbyn’s success as leader is whether conference becomes more powerful. When the Corbynites talk of making Labour more ‘democratic’, what they mean is curbing the influence of MPs by giving more power to conference. Their aim is to see it become the supreme policymaking body of the party. But to do that, they would have to outmanoeuvre the old right, which still holds many of the levers of power.

It would be easy for Labour’s moderates and reformers to expend their energies trying to work out how to stop the Corbynites fundamentally changing the party. But this would not be the best use of their time. Rather, they need to confront the more fundamental challenge of working out why Corbyn, a distinctly mediocre candidate, defeated them with such ease.

For the Blairite wing of the party this exercise is particularly painful. Despite them having led the party to three election victories, their candidate — Liz Kendall — received only 4.5 per cent of the vote in the leadership contest. Even worse for them is that this was the second Labour leadership contest in a row which has been won by the candidate rejecting New Labour and its approach.

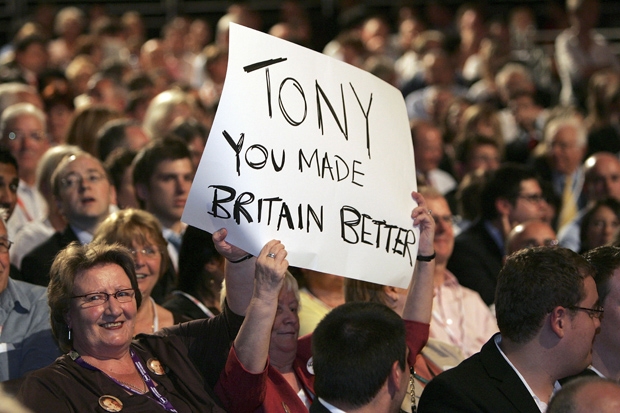

The temptation is to declare that Labour, like the Tories after Thatcher, are simply unable to come to terms with the legacy of their three-time election winner. But the truth is that with both Thatcher and Blair, the stumbling block wasn’t their record in office but how they have behaved out of it. The Tory problem with Thatcher was that after she was forced out of Downing Street she set about persuading her party that she had been a purely ideological, conviction politician — when she had in fact been a pragmatist when necessary. This led too many of her Tory supporters down an ideological cul-de-sac in an attempt to recapture her election-winning magic. The Blair problem is not with what he has said since he left office, but what he has done. His business dealings have given ample ammunition to those who think that New Labour was a betrayal of the party’s values. They have made it far easier for Blairism’s internal critics to suggest that the whole project was just about sucking up to the rich and powerful. ‘The loss of moral authority is the real killer,’ says one of those who is trying to keep the Blairitie flame alive.

Loss of moral authority has been compounded by lack of emotional intelligence. Too often, the Blairites have responded to any internal criticism by simply pointing to their election-winning record as if that should end all debate. They have reacted to their party’s electoral setbacks not with empathy but with a crude ‘I told you so’. As one leading backer of Liz Kendall admits, ‘We weren’t emotionally literate in our response’ to Labour’s general election defeat. The challenge for them is to find a way of reconnecting with the party that they want to lead. They need to re-establish that first Blairite coalition that included both the soft left and the modernising right.

Many have concluded, though, that the Blairite brand is now too toxic to rescue. Instead, they want to portray themselves as part of a longer Labour modernising tradition. Rather than to Blair, they look to Hugh Gaitskell. But the question is how many of them will obey his admonition to ‘fight and fight and fight again to save the party we love’. Reversing the hard left’s takeover will not be easy. It will require a new champion, a fresh set of arguments and the recruitment of 100,000 new, more moderate members. If they aren’t prepared — or able — to do that, Corbyn’s election will be the end of the Labour party as an election-winning force.

Comments