Stefan Zweig wasn’t, to be honest, a very good writer. This delicious fact was hugged to themselves by most of the intellectuals of the German speaking world during the decades before 1940, in which Zweig gathered a colossal and adoring public both in German and in multiple translations. It was like a password among the sophisticated. Zweig might please the simple reader; but a true intellectual would recognise his own peers by a shared contempt for this middlebrow bestseller. The novelist Kurt Tucholsky has a devastating sketch of a German equivalent of E.F. Benson’s Lucia:

Mrs Steiner was from Frankfurt, not terribly young, alone and with black hair. She wore a different dress each night and sat quietly to read cultured books. She was a devoted follower of Stefan Zweig. With that, everything has been said.

Some modern-day readers might find themselves agreeing with Zweig’s sniggering colleagues. His prose is apt to sink into the embarrassing commonplace. In his autobiography about the outbreak of war, he writes that the room

was suddenly deathly quiet…carefree birdsong came in from outside…and the trees swayed in the golden light…Our ancient Mother Nature, as usual, knew nothing of her children’s troubles.

Elsewhere, ‘the soft, silken blue sky was like God’s blessing over us; once again warm sunlight shone on the woods and meadows’. The odd thing was that, despite his immense success among readers who couldn’t hear enough about golden light in gardens and Mother Nature and silken skies like God’s blessing, Zweig was under no misapprehension about his own merits.

Talking about his art, Zweig had always denigrated it in a way much more like masochism than the sort of self-deprecation that invites contradictory praise. At the outset of his career, he had admitted that ‘at best my talent is a small one’. He was very much like Max Beerbohm’s Walter Ledgett: a bustling, friendly operator in the world of letters. His engagement with brilliant, original writers from the apparently safe standpoint of his luxurious schloss in Salzburg is untiring, despite their open jeering at their patron and host.

His relationship with the great, difficult writer Joseph Roth is a perfect example: there were almost no insults that Roth didn’t offer Zweig in exchange for his charitable support. Michael Hofmann, in his edition of Roth’s letters, says that ‘Eventually there is nothing that Roth will not write; a letter, in his hands, is an instrument of necessary terror.’ And Zweig took it all. He was heartbreakingly proud that when the Nazis burnt books in the Bebelplatz in 1933, he had the honour to be

permitted to share this fate of the complete destruction of literary existence in German with such eminent contemporaries as Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Franz Werfel and many others whose work I consider incomparably more important than my own.

In other circumstances, he would have been a comic figure, all mouth and trousers, in love with the orotund paragraph.With some amusement Carl Zuckmayer said that Zweig ‘loved women, revered women, liked talking about women, but he rather avoided them in the flesh’. But for a Jewish writer in Austria in the 1930s, the possibilities of remaining a comic figure were few.

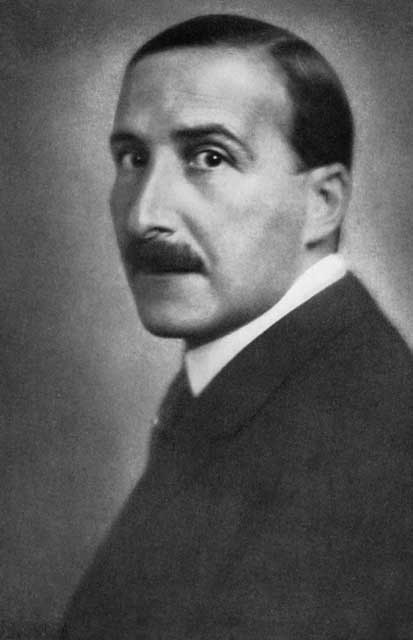

The flight from Austria that followed, and Zweig’s painful attempts to make sense of his own fate, are the subjects of George Prochnik’s study. The photograph on the cover (reproduced above) sets the tone: Zweig, the product of Viennese ‘Jewish bourgeoisie of the first rank throughout’, is exquisitely dressed and groomed, and looks simply terrified: he had received an uncompromising rejoinder to his plea that ‘all we ask is that we may not be bothered by politics’.

So the acclaimed cosmopolitan, whose books had gained an international readership, and who had enjoyed many successful press trips abroad, now prepared for exile, in another world of fame and respect, in Britain.

But it did not turn out quite as easy as that. Moving to Bath, Zweig found the English taciturnity at first enchanting. ‘Bath…soothes the eye more reliably than any other city in England, giving the illusion of reflecting another and more peaceful age, the 18th century.’ That feeling soon wore off, however. Was not this country, in fact, rather infuriating? Zweig clung to the renowned English love of gardening, as though afraid to venture into less charted areas of national behaviour. And there was always the terrifying thought that the Nazis were just across the Channel: invasion seemed inevitable, and escape would soon become impossible.

And eventually, like so many of them, he started to think that Freud might have been right when he said that ‘America is a mistake — a gigantic mistake, it’s true, but still a mistake.’ ‘You cannot imagine how I hate New York now, with its luxury shops, its “glamour” and splendour,’ Zweig said. But there was no possibility of returning to England, with U-boats targeting passenger ships. On a previous visit, Zweig had observed lightly: ‘Ice cream is really the best thing to be had in America.’ Soon he seemed to reach the limits of his endurance, and would have echoed another German writer, Martin Gumpert, who satirised the exile’s standard response as:So he proceeded to America. But in New York he found himself among thousands of other refugees. Though he was lionised and listened to as he had been on former visits, he now found himself cast as a spokesman for a whole group of people he regarded with contempt, as beggars and spongers. The dismissive word Schnorrer enters his letters when he writes of his fellow exiles.

There are no trees…there are no cafés here…there are no villages, no inns, no meadows, no crooked little streets…no Alpine valleys, no real mountains, no real seashore.

Furthermore, his views, eagerly sought out by pundits, started to seem pathetically inadequate. Was a national Jewish homeland necessary? No, he thought: the Jew was ‘the gadfly that plagues the mangy beast of nationalism’. Zweig claimed that he

never wanted the Jews to become a nation again and thus to lower themselves to taking part with the others in the rivalry of reality. I love the Diaspora and affirm it as the meaning of Jewish idealism, as Jewry’s cosmopolitan human mission.

That response may have been noble and idealistic but it was wholly out of touch with reality, and would find no followers in the 1940s.

Zweig moved again to the (then dreary) New York suburb of Ossining, and in 1941 finally retreated to Petró-polis, in the mountains near Rio de Janeiro. There he wrote a desperately sad, banal autobiography which he considered calling Europe Was My Life, and a lamentable book about Brazil, Land of the Future, in which he seriously described Rio as a ‘city of contrasts’. One day he lay down with his young wife and committed suicide. Whether that was out of despair, or partly because he felt that it would be a romantic gesture, readers may speculate.

Prochnik’s rambling biography is oddly structured, circling round the facts of Zweig’s exile in a way that requires one to untangle the events chronologically for oneself. He also discusses his own family’s experiences, without confronting the obvious truth that the elegant Zweig would not have considered Prochnik’s own father — had they ever met — as an equal compatriot. The book would have benefited from a proper account of the brilliant period of Zweig’s career, which is quickly passed over for the poignant details of a literary man of limited resources trying to make sense of Ossining.

Still, the story is a touching one; and Zweig appears to be becoming fashionable and popular again. Wes Anderson’s film The Grand Babylon Hotel is inspired by the general style of his work. (A genuinely original writer in exile, like Joseph Roth or Thomas Mann, would never be able to command this sense of shared sentiment.) With his ordinariness, his shrug, his land-of-contrasts clichés and his beautiful jackets, Zweig may always provide something to which most people can easily respond.

Comments