Imagine living in a country where a politician could not only force a newspaper to retract a report but could then make it publish an alternative report on its front page. That would be a bad place to live, right? It would be a place where the relationship between the press and politicians — where the former is supposed to keep in check the latter, not the other way round — had been twisted beyond repair. It would be a country in which pressmen and women would be always on edge, fearful that if they were too stinging or scurrilous about a political player then they, too, might be forced into a humiliating climbdown. And no one benefits when the press quivers before the powerful. Except, of course, the powerful.

Well, I’m afraid to tell you that, if you’re a British-based reader of the Spectator website, you already live in this country.

This week, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso) upheld a complaint against the Telegraph by Ivan Lewis, Labour MP and former shadow secretary of state for Northern Ireland. In August, during the Labour leadership contest, the Telegraph published a report headlined ‘Labour grandees round on “anti-Semite” Corbyn’. The report quoted from an article written by Lewis, in which he had rebuked Corbyn for rubbing shoulders with anti-Semites but did not accuse Corbyn of being an anti-Semite. Lewis’s article said Corbyn had ‘shown poor judgement in expressing support for and failing to speak out against people who have engaged in… anti-Semitic rhetoric’. But the Telegraph suggested Lewis actually called Corbyn anti-Semitic. That was wrong. And Lewis was annoyed.

In which case, why did he not simply write a letter to the Telegraph to expose its misinterpretation of his remarks? Why did he not simply use his considerable clout as an MP, and then member of the shadow cabinet, to restate his case on Corbyn? It’s not as if Lewis lacks platforms. Yet instead he went to Ipso, the post-Leveson body that replaced the allegedly ‘toothless’ Press Complaints Commission and which, in contrast to the PCC, has teeth. Ipso has now slammed the Telegraph and instructed it to publish a correction on page 2 of its paper and — get this — to refer to the correction on page 1. Through a complaints body, a politician has just pressured a newspaper to print something on its front page. I can’t be the only person who finds this alarming.

It is testament to the chilling effect of the post-Leveson climate that even writing the following makes me feel nervous: it seems to me that Lewis was more interested in punishing the Telegraph than in correcting its story. If that’s right — and I am very open to the possibility that it isn’t; just please tell me in the comments section below rather than via Ipso — then he isn’t alone.

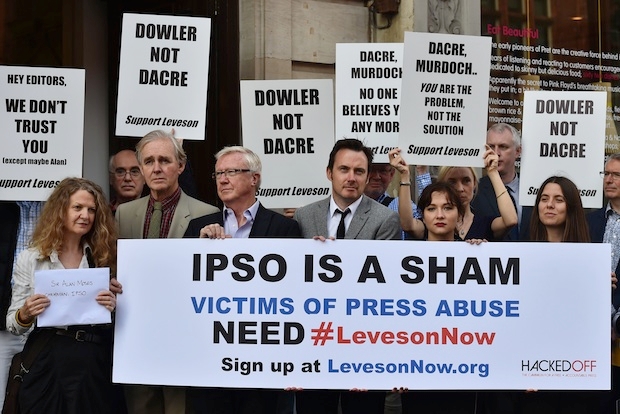

Ipso acts as a permanent invitation to the tut-tutters of Tunbridge Wells, to press-haters everywhere, to try their hand at punishing the press for what they consider to be its wrong or wicked or daft claims. An independent regulator — in the sense that it isn’t underpinned by statute — it has been signed up to by most of the major news groups. They all boast that Ipso is ‘Leveson-compliant’ — a bit like turkeys at Christmas time boasting of being ready to have stuffing shoved up their backsides.

Ipso is a finger-waggers’ wet dream, a complainers’ charter. It allows third parties and ‘representative groups’, not just those directly affected by a story, to make a complaint. And it can dictate how newspapers found guilty of giving offence or making a misrepresentation must atone for their sins: it can instruct them about the wording of their retractions and even tell them where they must be published in the paper. The Sun was censured after Rod Liddle made a joke about a trans person; the Belfast Telegraph was investigated for publishing a letter saying Poles bear responsibility for what happened in their nation during the Holocaust. So everything from gags to political opinion is being looked into by Ipso. Even if complaints aren’t successful, journalists’ time is being sucked up in dealing with them: Andrew Gilligan, for example, says he now spends ‘a day or two’ each month dealing with Ipso complaints, largely in relation to his work on Islamist groups.

This is what Leveson has wrought: a war on the press, not with jackboots and guns, but through the institutionalisation of complaint. We’re all now invited to throw rotten metaphorical tomatoes at the press. Now even a politician with plenty of ways to correct wrong or bad info is contributing to this chilling of press freedom. Lewis’s actions have set a worrying precedent. They could make press people think twice before harshly critiquing politicians, and encourage other politicians to use Ipso to get one over on the press.

Three-hundred-and-fifty years ago, Levellers, liberals and hacks fought to free their pamphlets and papers from the censorious grip of the powerful. It seems that war might have to be refought. I know which side I’ll be on: that of the press, regardless of how rude or nasty it can be. Press freedom is infinitely more important than the feelings or reputation of politicians.

Comments